http://www.thejakartapost.com/news/2014/08/20/jilboobs-a-storm-a-d-cup.html

Julia Suryakusuma

Like most women, Muslim women want to be seen as physically attractive. Many also like to be seen as pious. These two things are often perceived as being contradictory, so how do we reconcile them? Simple: Wear a “jilboob!”

A whaaat? Yes, the jilboob, a contraction of jilbab (Muslim headscarf) and boobs (breasts), a term Indonesians use to refer to Muslim women who wear the headscarf but at the same wear clothes that accentuate their curves — in particular their bust. Obviously, “jilboobers” believe, “when you’ve got it, flaunt it”!

And all this time you thought the jilbab was worn to guard women’s modesty huh? Well, think again!

Mark Twain once said “clothes make the man” and they obviously make the woman as well.

What we wear determines our identity, so are jilboobs a clever way for women to merge their religious, gender and sexual identities? Are they being hypocritical by doing so? After all, they are covering everything but, in fact, hiding nothing.

I’m actually surprised that the jilboob phenomenon has only become controversial now, as it’s

been around for almost 10 years. Maybe it’s because the ranks are expanding (and the boobie sizes increasing!).

Why, there are even jilboobers Facebook fan pages, as well as twitter hashtags. Check them out!

One way or another, the jilbab has often generated controversy. There was the political/ideological jilbab, worn as a symbol of resistance when the New Order was repressing Muslim groups.

In the reform era, there was the obvious trend of jilbabisasi (jilbabization) with increasing numbers of women wearing them as an expression of Islamic identity and a reaction to a perceived influx of westernization.

And if previously jilbab was donned by rural and uneducated women, in the reform era it became fashionable for the well-heeled, businesswomen, officials and intellectuals to wear it.

Different styles of jilbab quickly emerged: Jilbab gaul (jilbab for hanging out), jilbab trendi (trendy jilbab) and jilbab modis (stylish jilbab). High-fashion designers, such as Ghea, Barli Asmara, Biyan and Carmanita, among others, have been cashing in on the booming trend, with each making their own particular style of busana muslim (Muslim wear).

All take care to adhere to the prescribed, commonly understood Islamic standards of modesty and not reveal the shape of the female body.

But now you have jilboobs that do. What gives? Jilboobs are simply the convergence of trends toward religiosity in Indonesia with globalization, which brings with it Western standards of beauty — currently obsessed with big boobies.

Just look at female Hollywood celebrities: Pamela Anderson, Victoria Beckham, Salma Hayek, Jessica Simpson, Beyoncé, Halle Berry, Dolly Parton, and, of course Heidi Montag. All have (reportedly) had breast augmentations.

In Hollywood, it’s de rigueur to “accessorize” yourself with big breasts, in the same way that it’s de rigueur to accessorize with expensive designer handbags and shoes. And in an era when celebrities are role models, it’s not surprising that big breasts have become a fashion item.

According to a plastic surgeon I know, she can do up to 15 breast augmentations per month, and the trend is on the rise. In Indonesia, it’s not just celebrities like Krisdayanti, Julia Perez or Farah Quinn who get them, but also ordinary folks: Young women who claim their breasts are sagging due to breastfeeding, or who are about to get married and want to be more appealing to their husbands.

Women want to show off their assets, whether natural or unnatural. So if you’ve paid a truckload of money to get your breasts blown up, naturally you want to expose (sic!) them.

But what about your Muslim identity which you also want to show off too? Easy — throw a piece of cloth over your head, but do it fashionably!

So many Indonesian celebrities are doing it too that many feel they’ve got to follow the trend! And that’s all the jilboob is: a fashion trend.

Predictably, the Indonesian Ulema Council (MUI) reacted in a knee-jerk manner, issuing a fatwa saying jilboobs are haram (forbidden by Islamic law).

It’s the usual reaction: A bunch of men trying to show their power by using religion to tell women how to dress and behave.

How about lowering your gaze guys, instead of staring at those lovely breasts? What about making boobie-ogling haram instead, you MUI men?

But is wearing a jilbab really a must for Muslimahs (Muslim women) according to Islam?

It’s seen as a given that it’s wajib (obligatory) for Muslim women to wear a jilbab. Hardly anyone asks any questions, when in fact many could — and should. Why and by whom were women told to wear jilbab/hijab? What’s the history behind it?

Why do women have to cover up their aurat (forbidden parts), which for them is from head to toe, while for men it’s only from the waist to the knee?

One woman who did ask was Nong Darol Mahmada, one of the members of Jaringan Islam Liberal (JIL, Islam Liberal Network) who wrote a thesis on the subject.

She found that although the answer is not black and white, basically the jilbab is a cultural tradition, not a religious obligation.

It’s also a political power construct. She points out that in Indonesia, the first visual indicator that a region is implementing sharia is the introduction of compulsory wearing of jilbab, complete with a body (sic!) to oversee women, to make sure they adhere to the “Muslim dress code”. “As if jilbab is Islam itself”, she says.

For me, jilbab all too often stands for little more than the superficialization of Islamic precepts, the hypocrisy of many Muslims (both men and women), and even the idolizing of a rule that may not even be a rule at all.

So what’s the fuss about jilboobs? It’s simply a storm in a bra cup!

Wednesday, August 20, 2014

Tuesday, August 19, 2014

Racism and Schadenfreude What is Ferguson doing on Europe's front pages?

http://www.economist.com/blogs/democracyinamerica/2014/08/racism-and-schadenfreude?fsrc=scn/fb/wl/bl/whatisfergusondoinoneuropesfrontpages#

by M.S. | AMSTERDAM

I WOKE up today to find my Dutch morning paper, the Volkskrant, dominated by a full-page spread on the results of the independent autopsy on Michael Brown, the shooting victim whose death has plunged the town of Ferguson, Missouri, into protests and riots. The situation in Ferguson also headlined today's editions of Spain's El Pais, Portugal's Publico, Denmark's Politiken, France's Liberation, and Germany's Der Tagespiegel, Die Tageszeitung and Die Welt. The racially charged protests over police brutality in Ferguson are an important story, but the level of attention they are drawing in Europe is frankly bizarre. Police killings of unarmed black men occur regularly in America, and Ferguson is a small, faraway midwestern town. Yet the protests there are drawing more focused attention in northern European media than the anti-austerity riots in Greece did during the euro crisis. When Paris saw anti-Semitic riots following pro-Gaza demonstrations on July 13th, it did not even make a sidebar item on the front page of the next day's Die Welt.

Admittedly, Germany's football team had just won the World Cup that day. (I wasn't able to find archival imagery on whether stories on the Paris riots had made front pages in, say, the Netherlands or Italy.) Besides, there is often a strange feeling of regional dissociation in Europe; many countries feel themselves closer to current events in America than to those in neighbouring countries. Young Dutch certainly seem to know more about politics in America than in France or Italy. Still, this has not been a summer that has lacked for news. On Monday the Ukrainian army was taking over Luhansk, the Kurds were reconquering the Mosul dam from ISIS, Israel and Hamas were still locked in negotiations over extending their ceasefire, and the WHO announced that the number of Ebola victims had topped 1,200. All of these stories are closer and more relevant to Europeans than issues of racial justice in the St Louis suburbs. So what is Ferguson doing on Europe's front pages?

Part of the attraction of the Ferguson story for Europeans may be a bit of Schadenfreude enjoyment of America's racial woes. Europeans got tremendous political mileage out of America's racial conflicts in the 1960s, using American racism as a negative pole to rally support for counter-American projects both on the Gaullist right and on the socialist left. In recent years it has been Europe that has struggled with anti-immigrant racism and an integration model that seems to work much worse than America's. Europeans weary of criticism over rising xenophobia may be relieved to see that America still has its own troubles.

In a similar fashion, countries such as China, Russia, Egypt and Iran are exploiting the Ferguson riots to try to blunt human-rights criticism of their own repressive activities. "Obviously, what the United States needs to do is to concentrate on solving its own problems rather than always pointing fingers at others," huffed an editorial published by Xinhua on Monday. "We would like to advise our American partners to pay more attention to restoring order in their own country, before imposing their dubious experience on others," Russia's foreign ministry declared Friday.

This sort of nonsense essentially recaps scripts developed by the Soviet Union in the 1960s and '70s, and there's nothing to say about it except that it should be entirely disregarded. Racism is far more ubiquitous, deep-seated and reflexive in both China and Russia than it is in America or western Europe, precisely because events like those in Ferguson lead America to engage in a soul-searching national debate, while similar events in Russia and China generally lead either to no internal self-examination, or to a hardening of racial animosities. Persistent racial discrimination and prejudice in America should not lead America or other countries to be any less harsh in their condemnations of China's treatment of Tibetans and Uighurs, or of Russia's treatment of Chechens, Dagestanis, Roma, Vietnamese, etc.

That said, there's another reason why the events in Ferguson are so interesting to a European public, and for that matter to everyone else. The confrontation in Ferguson, as many observers have noticed, looks uncannily like the ones in Ukraine, Gaza and Iraq. There is clearly some kind of a global blowback going on, in which military techniques of forcible population control developed for use at the periphery of states' areas of sovereignty are now being applied at the centre. Leonid Bershidsky, a brilliant Russian journalist and editor, laid out the similarities in a fascinating column yesterday in Bloomberg View. "Police officers around the world are becoming convinced they are fighting a war on something or other, whether that's drugs, terrorism, anarchists or political subversion," Mr Bershidsky writes. "This mindset contrasts with the public's unchanged perception of what the police should be doing, which is to keep the streets safe, a conceptual clash that can lead to unexpected results."

The difference between these two kinds of policing, Mr Bershidsky writes, can be modeled as the division between the London Metropolitan Police Force established in 1829, which conceived itself as fighting crime in concert with the populace, and the repressive colonial police forces the British Empire employed in "colonies of rule" such as Ireland and India, who conceived of themselves as keeping potentially hostile local populations in line. He cites the argument of Emma Bell, a faculty member at France's Universite de Savoie, that the colonial policing culture is now "coming home", as local police forces come to see themselves as hostile to the populations they police. And he recalls how militarised police provoked the conflict in Ukraine.

On Nov. 30, the Berkut riot police beat up a few hundred students who had camped on the main square of the capital, Kiev, to call for closer ties between Ukraine and Europe. Ukrainians were not used to being treated like the population of a "colony of rule." Hundreds of thousands took to the streets the following day, setting off a chain of events that led to the overthrow of President Viktor Yanukovych and the current crisis on Europe's eastern borders.I am not entirely convinced that Mr Bershidsky is right that increasing the level of militarisation of the police response in Ferguson will have the opposite of its intended effect. Ferguson's own police force may have been heavily militarised, but they were also untrained and incompetent. Better trained and more efficient militarised police have been highly successful at containing and shutting down popular protests in New York, Moscow, Cairo and so on. The depressing reality is that, as repressive as modern police tactics of population control may be, they seem to be very effective, and the boundaries for autonomous civic action are growing ever narrower. Indeed, even as Ferguson was featuring on the cover of today's Volkskrant, the paper was also reporting on efforts by the mayor of The Hague to ban an anti-ISIS march by Dutch right-wingers in a largely Muslim neighbourhood, after an earlier march led to violent clashes. Europeans are right to be riveted by what's happening in Ferguson. It is in the same genre as the stories of protest and control we see playing out all over the world.

That reaction helps to explain why the heavily armed police in Ferguson, Missouri—who looked more threatening and wore more tactical armor than U.S. servicemen in Iraq—were unsuccessful. Now they are to be aided by the National Guard, which is paramilitary by definition.

Arming police with military weaponry and outfitting them for battle is a recipe for creating violent conflict where there was none and achieves the opposite of keeping public order.

Jangan Sampai Sejarah Fernando Lugo di Paraguay Terulang pada Jokowi di Indonesia

http://politik.kompasiana.com/2014/08/16/jangan-sampai-sejarah-fernando-lugo-di-paraguay-terulang-pada-jokowi-di-indonesia-668730.html

Daniel H.t.

Daniel H.t.

Budiman Sudjatmiko baru kali ini benar-benar merasa ketakutan. Takut akan mati! Perasaan itu muncul begitu saja, ketika dia menghadapi pengalaman yang sangat luar biasa itu. Membayangkan sebagai ide untuk membuat kisah fiksi pun tak pernah terpikirkan. “Real life is stranger than fiction”, kata Budiman kemudian ketika mengisahkan kembali pengalaman luar biasanya itu.

Saat itu Budiman yang sekarang adalah anggota DPR dari PDIP, salah satu pencetus utama ide lahirnya UU Desa, merasa heran sendiri, kenapa perasaan takut mati itu bisa begitu saja muncul dari dalam dirinya. Padahal dahulu, terutama di tahun-tahun 1996-1998 ketika dia adalah salah satu aktivis politik anti-Soeharto, yang memperjuangkan reformasi dan tegaknya demokrasi di Indonesia, akibatnya dia diburu-buru intel-intel Soeharto, dia tidak pernah merasa takut mati.

Di masa-masa itu Budiman selalu menjadi salah satu target utama intelijen rezim Soeharto, BIA (Badan Intelijen ABRI) dan Bakorstanas (Badan Koordinasi Bantuan Pemantapan Stabilitas Nasional), apalagi ketika dia membentuk Partai Demokratik Demokrat (PRD).

Bersama beberapa orang sahabatnya Budiman pernah diculik, disekap, dan diinterogasi dengan cara-cara yang kejam ala Orde Baru. Beberapa sahabatnya itu ada yang sampai tewas, dan ada yang tidak pernah kembali sampai hari ini. Mereka adalah bagian dari tiga belas aktifis yang sampai sekarang masih hilang itu. Ketika itu, menghadapi saat-saat yang paling mencekam, ketika nyawa sudah berada di tepi jurang kematian, Budiman mengaku tak ada dalam pikirannya untuk takut mati.

Budiman dan beberapa temannya dari PRD ditangkap terakhir kali oleh rezim Orde Baru, pasca peristiwa kerusuhan penyerbuan gedung DPP PDI, pada 27 Juli 1996. Mereka dijadikan kambing hitam sebagai otak dari kerusuhan itu. Budiman divonis penjara 13 tahun. Dibebaskan ketika Soeharto lengser, digantikan B.J. Habibie.

Ketika selama bertahun-tahun selalu diincar maut di masa-masa itu, Budiman seolah tidak punya rasa takut mati. Tetapi, kenapa sekarang dia menjadi takut mati? Budiman juga tidak bisa menjawabnya, karena perasaan takut mati itu begitu saja muncul ketika dia terjebak di dalam peristiwa yang sangat luar biasa itu.

Peristiwa itu terjadi pada tengah malam di tanggal 13 Agustus 2008, 6 tahun yang lalu, di sebuah negara yang nun jauh di sana. Di Republik Paraguay, tepatnya di Ibukota di salah satu negara Amerika Latin itu, Asunction!

Sekitar pukul 3 dini hari, mereka berempat berada di dalam sebuah mobil yang melaju dengan kecepatan tinggi, melebihi 100 km per jam, membela kota Asunction yang telah lelap. Kondisi jalan yang naik turun, membuat beberapakali mobil itu sesaatmelayang di udara. Setiap kali mobil itu melayang di udara, jantung mereka punseolah-olah ikut melayang dari raga.

Mereka berempat itu adalah Budiman Sudjatmiko dan Rikard Bangun (sekarang pimpinan Redaksi Harian Kompas), dua orang ini duduk di jok belakang mobil tersebut, seorang Romo asal Flores, Indonesia, Romo Martin Bhisu, duduk di samping sopir, dan si sopir itu. Budiman duduk persis di belakang sang sopir yang masih terus menginjak dalam-dalam pedal gas mobil itu. Sopir mobil inilah yang membuat peristiwa itu menjadi berlipatganda luar biasanya, yang tidak mungkin bisa dilupakanmereka semua. “Real life is stranger than fiction”, Budiman mengistilahkan pengalamannya itu. Kenapa demikian? Karena sopir itu bukan lain adalah presiden terpilih Republik Paraguay, Fernando Lugo, yang dua hari lagi akan dilantik!

Budiman dan Rikard sangat bingung dan saling bertanya apa yang sebenarnya sedang terjadi ini? Apa sebenarnya yang sedang dihindari Fernando Lugo, dan kenapa harus dia yang dua hari lagi resmi dilantik sebagai Presiden Paraguay itu harus mengemudi sendiri mobilnya? Nasib apa yang membuat mereka berdua yang baru hari dan kali pertama meninjak kaki di Paraguay, langsung mengalami peristiwa ini bersama dengan seorang presiden terpilih negara itu?

Ketika mobil itu masih terus melaju dengan kecepatan di atas 100 km per jam, Romo Martin dan Fernando Lugo terdengar berkomunikasi dalam bahasa Spanyol, sehingga Budiman dan Rikard tidak mengerti apa yang sedang mereka percakapankan itu. Namun dari percakapan itu, dia sempat menangkap beberapaka kali kata yang bunyinya seperti “golpe” Budiman berpikir sejenak, kemudian terkejut luar biasa, ketika ingat bahwa arti kata dalam bahasa Spanyol itu adalah “kudeta”! “Apa!? Kudeta!?”

Kemudian Romo Martin menjelaskan kepada Budiman dan Rikard bahwa saat ituternyata ada rencana pembunuhan terhadap Fernando Lugo! Karena itu sekarang diamelarikan diri dari rumahnya tadi! Kebetulan sekali, dua tamunya dari Indonesia itu yang awalnya punya rencana hendak mewawancarainya itu, pun “terjebak” di dalam peristiwa tersebut.

“Tapi, bukankah ada pasukan pengawal kepresidenan yang mengawalnya?” Tanya Budiman kepada Romo Martin. Romo Martin menjelaskan, Lugo mendapat informasi bahwa justru di antara para pengawal itulah ada eksekutor yang akan membunuhnya! Maka itulah dia langsung melarikan dirinya dengan mengemudi mobilnya sendiri, dan beginilah mereka sekarang.

Budiman menjadi semakin khawatir, bagaimana jika terjadi apa-apa dengan mereka? Bagaimana jika mobil yang sedang melaju dengan sangat kencang itu tiba-tiba menabrak sesuatu yang keras, atau mereka mati terkena peluru nyasar dalam suatu aksi tembak-menembak ketika kudeta terjadi? Lalu, seantero Amerika Latin pun akanheboh luar biasa, bergetar-getar menyatakan penuntutan balas atas kematian sang sopir. Amerika Latin bisa diselimuti duka sekaligus mengalami keheranan luar biasa: Kenapa kecelakaan itu terjadi dan kenapa bisa ada tiga jenazah orang Indonesia bersama presiden mereka yang juga tewas itu? Kenapa sang presiden terpilih yang mengemudi mobil itu?

Akhirnya, keempat orang itu tiba di lokasi yang menjadi tujuan Fernando Lugo, yaitu sebuah Rumah Induk dari SVD (Sociedad de Verbo Divino), sebuah ordo Katholik yang banyak terdapat di Amerika Latin. Di situlah Fernando Lugo untuk sementara mengamankan dirinya.

Romo Martin kemudian menjelaskan dengan lebih detail kepada Budiman dan Rikardtentang peristiwa apa yang sebenarnya sedang mereka alami itu. “Ada upaya pembunuhan terhadap Lugo,” katanya mengulangi penjelasannya di mobil tadi itu.

“Siapa yang mau membunuhnya, Romo?” Tanya Rikard.

“Oligarki yang tidak suka Fernando Lugo menang pemilihan presiden. Mereka tidak ingin Lugo dilantik besok lusa.”

“Siapa oligarki itu?” Tanya Budiman.

“Siapa lagi kalau bukan tuan tanah, para pengusaha hitam, politisi-politisi konservatif dan sejumlah perwira militer loyalis kandidat presiden yang kalah, Lino Oviedo?”

Fernando Lugo adalah mantan uskup. Ketika dia menjadi uskup, dia banyak membela rakyat miskin, terutama petani-petani yang tanahnya banyak dirampas oleh tuan-tuan tanah yang berkomplot dengan penguasa sipil dan militer. Maka, dia pun dijuluki oleh rakyat Paraguay dengan sebutan “Uskup Orang Miskin.” Setelah dia terpilih menjadi presiden pun mereka menyebutkannya dengan sebutan “Presiden yang merakyat.”

Karena desakan rakyat semakin kuat, dan dia sendiri berpikir bahwa perjuangannya untuk mensejahterakan rakyat Paraguay, dan menjadikan Paraguay yang baru, akan bisa lebih maksimal jika dia menjadi presiden, maka Lugo pun memutuskan untuk mencalonkan diri sebagai presiden di Pemilu Presiden Paraguay di tahun 2008 itu.

Lugo kemudian mengundurkan diri sebagai uskup. Awalnya, permohonan pengunduran dirinya sebagai uskup itu, ditolak Vatikan, tetapi rakyat Paraguay pun “mengancam” Vatikan, apakah hendak mendapatkan satu orang Lugo yang tetap menjadi uskup, tetapi kehilangan jutaan umat Katholik di Paraguay, ataukah kehilangan satu orang uskup, tetapi tetap diikuti oleh jutaan umat Katholik di Paraguay. Vatikan akhirnya mengabulkan permohonan mundur Lugo sebagai uskup itu.

Budiman dan Rikard kemudian diundang juga menghadiri pelantikan Fernando Lugo sebagai Presiden Paraguay pada 15 Agustus 2008.

Segera setelah dilantik sebagai Presiden, Lugo langsung bergerak mengeluarkan beberapa dekrit dan mengadakan beberapa kebijakan baru untuk mulai melakukan perubahan-perubahan penting. Lugo langsung membuktikan perkataannya saat pidato pelantikannya sebagai Presiden, “Orang harus membayar apa yang telah mereka curi!”

Budiman dan Rikard menyaksikan sendiri bagaimana Lugo bergerak begitu cepat sesaat setelah dilantik, dia memeriksa dan menandatangani berbagai dekrit, di antaranya mengenai reformasi birokrasi yang merupakan salah satu yang terkorup di dunia, distribusi tanah untuk petani tak bertanah, penanganan kaum Indian, dan sebagainya, di hadapan sejumlah calon menterinya. Tidak lebih dari dua puluh empat jam setelah pelantikannya, dia langsung membuat kebijakan terobosan politiknya pada hari Minggu.

Saat Budiman bertanya kepadanya, “Mengapa kebijakan-kebijakan strategis seperti itu langsung dibuat bahkan sebelum pelantikan kabinet?”, calon Menteri Sekretaris Negara, Luis Perito, segera menyahut:

“Kita sekarang sudah berkuasa. Dari ruangan ini (Istana Negara), sudah sangat lama para penguasa mengeluarkan kebijakan-kebijakan yang menyengsarakan rakyat. Menunda untuk dua puluh empat jam lagi setelah penantian lama 197 tahun tak bisa kami tolerir lagi!”

Budiman menulis renungannya, “Aku tersenyum haru untuknya dan untuk rakyat negerinya. Tapi pada saat yang sama aku tertegun seraya menelan ludah untuk tanah airku sendiri. Saat itu aku teringat, sangat ingat bahkan, bagaimana perubahan politik di tanah airku sendiri justru dibajak oleh unsur-unsur rezim lama. Ada ironi yang aku telan saat menyaksikan Lugo mulai memimpin Paraguay, pada suatu hari Minggu yang penuh semangat.”

Demikianlah kisah di atas saya sari dari buku yang ditulis oleh Budiman Sudjatmiko, yang berjudul Anak-anak Revolusi, Jilid 2, Penerbit Gramedia, 2014, Bab 14 dan 15.

“Orang harus membayar apa yang telah mereka curi!” Itu antara lain pernyataan Presiden yang bernama lengkap Fernando Armindo Lugo Mendez itu, yang dikutip Budiman Sudjatmiko di bukunya itu. Dan, seperti yang dituturkan Budiman, Lugo langsung menggebrak, membuktikan kata-katanya itu, segera – hanya empat jam setelah dilantik, bahkan saat di hari Minggu. Gebrakan Lugo itu boleh dikatakan melawan arus di negaranya yang selama puluhan tahun sudah membudaya dengan kebiasaan korupsi, kolusi, dan nepotisme (KKN) yang dilakukan oleh para penguasanya yang berasal dari Partai Colorado. Sebuah partai politik sebelumnya telah sangat berkuasa selama 61 tahun, yang mirip dengan Golkar di Indonesia di masa Orde Baru.

Selama bertahun-tahun itu pula setiap penguasa di Paraguay sudah “biasa” berkomplot dengan korporasi-korporasi besar, baik di dalam negeri, maupun dari luar negeri, terutama Amerika Serikat untuk menguras kekayaan negaranya sendiri demi memperkaya dirinya sendiri dan komplotannya.

Bisakah Fernando Lugo mengubah semuanya, yang berarti melawan arus yang pasti sangat kuat luar biasa itu? Dengan demikian musuh-musuhnya pasti sangat banyak, dan sangat kuat.

Ketika itu, gebrakan yang dilakukan oleh Fernando Lugo sudah mendapat peringatan dari Presiden Ekuador Rafael Correa. Dengan cemas dia mengingatkan, “Begitu Lugo mulai mengubah berbagai hal, serangan akan dimulai!” Serangan dimaksud berasal dari para kapitalis, politikus dan koruptor, termasuk mereka yang selama ini berkoloborasi dengan cara-cara kotor bersama dengan korporasi-korporasi raksasa asal Amerika, yang dilakukan dengan menghalalkan segala cara.

Para pakar politik Amerika Latin pun sudah memprediksi bahwa Lugo akan menjalani masa-masa yang sangat berat untuk mempertahankan posisinya sebagai presiden. Bukan tak mungkin Partai Colorado akan berkuasa kembali, jika pemerintahan koolisi yang dipimpin oleh Lugo itu gagal meredam anarkisme yang timbul akibat euforia di kalangan petani miskin. Segera setelah Lugo dipastikan terpilih sebagai presiden, para petani tanpa tanah langsung menyerobot tanah-tanah pertanian yang diukuasai perusahaan-perusahaan besar, sehingga menimbulkan berbagai gejolak sosial. Kasus-kasus seperti ini terus terjadi selama Lugo berkuasa.

Serangan yang diperingatkan Presiden Ekuador Rafael Correa itu benar-benar terjadi, hanya sehari setelah Lugo dilantik sebagai presiden baru, yang seharusnya berkuasa dari 2008-2013. BBM dan obat-obatan mendadak hilang dari pasaran, sehingga sempat menimbulkan krisis.

Puncaknya terjadi pada 2012.

Memanfaatkan terjadinya bentrokan berdarah salam suatu kasus sengketa tanahantara polisi dengan para petani yang menyebabkan tewasnya 10 petani dan 7 polisi, setelah melewati beberapa sidangnya yang dilakukan dengan tergesa-gesa, Senat Paraguay yang dikuasai partai oposisi memutuskan menjatuhkan kesalahan kepada Lugo.

Dia dinyatakan bersalah karena gagal menjalankan tugasnya sebagai presiden, dan pada 22 Juni 2012 mandatnya sebagai Presiden Paraguay dicabut Senat. Meskipun, sebelumnya delegasi dari Union of South American Nations (UNASUR) telah datang ke Asunction untuk bertemu dengan pihak pemerintah dan oposisi, dan memperingatkan oposisi bahwa akan terjadi “kudeta kamuflase” jika Lugo dilengserkan.

Pencopotan Lugo sebagai Presiden itu sempat menimbulkan demonstrasi besar-besaran di berbagai kota di Paraguay, terutama di Ibukota Asunction. Untuk menghindari konflik dan hal lain yang lebih buruk lagi, Lugo menyatakan menerima pemecatannya itu, “Saya mengucapkan selamat. Demokrasi di Paraguay saat ini sudah terluka,” ujar Lugo usai Senat memutuskan pemecatannya itu.

Setelah Lugo dilengserkan Senat, Wakil Presiden Frederico Franco yang berasal dari Partai Liberal Radikal, naik menjadi Presiden menggantikannya. Di awal kekuasaan Lugo, Franco selalu menyatakan dukungannya terhadap program-program Lugo. Ketika pemerintahan telah berjalan beberapa tahun, mulai tampak adanya perbedaan-perbedaan pendapat antara Lugo dengan Franco. Di saat-saat Lugo harus berhadapan dengan Senat, Franco memilih berpihak kepada Senat, sehingga mempermudah jatuhnya Lugo dari kursi kekuasaannya itu.

Naiknya Frederico Franco menjadi Presiden Praguay mengganti Ferdando Lugo itu tidak mendapat pengakuan dari beberapa negara tetangga Paraguay, di antaranya Presiden venezuela Hugo Chaves dan Presiden Ekuador Rafael Corea.

Frederico hanya berkuasa dari 22 Juni 2012 – 15 Agustus 2013, atau sama dengan menghabiskan masa jabatan sebenarnya dari Lugo. Setelah itu, apa yang dikhawatirkan banyak pihak pun terjadi, dengan berkuasanya kembali Partai Colorado dengan presidennya Horacio Cartes, dan Wakil Presiden Juan Afara, juga dari Partai Colorado.

*

Fenomena politik yang terjadi di Paraguay dengan tokoh utamanya Fernando Lugo di era 2008 - 2012 itu mirip-mirip dengan fenomena politik yang terjadi di Indonesia saat ini dengan tokoh utamanya Jokowi.

Seperti Fernando Lugo, Jokowi juga dikenal sebagai presiden terpilih yang benar-benar berasal dan berjuang demi rakyat. Jokowi juga disebut sebagai “Presiden Rakyat”, atau “Presiden Rakyat Miskin”.

Sejak memulai starnya sebagai calon presiden, Jokowi sudah melakukan gerakan yang melawan arus, dan kebiasaan yang selama ini telah “membudaya” selama puluhan tahun di pemerintahan Republik Indonesia. Dia menyatakan dengan tegas semua parpol, atau pihak mana pun yang hendak berkoalisi dengannya harus menerima syarat terlebih dulu bahwa koalisi dilakukan bukan berdasarkan komitmen bagi-bagi kekuasaan. Belajar dari sejarah, Jokowi tak ingin tersandera oleh parpol-parpol politik dengan politik balas-jasa, hutang budi, dan politik dagang sapi, yang hanya mengerus hak-hak prerogatifnya jika terpilih sebagai presiden, yang pada akhirnya membuat pemerintahan berjalan tidak efektif, sibuk mengatasi konflik internal, dan sebagainya. Bahkan bisa terjerumus pada praktek KKN juga.

Setelah pada 22 Juli 2014, begitu dipastikan oleh KPU sebagai pemenang Pilpres 2014, yang berarti Jokowi dan JK akan secara resmi memangku jabatan Presiden dan Wakil Presiden untuk masa jabatan 2014-2019, setelah dilantik pada 20 Oktober 2014 mendatang, Jokowi tidak mau membuang-buang waktu lagi, dia langsung bergerak cepat – meskipun saat ini sidang gugatan hasil Pilpres masih berlangsung di MK, tetapi Jokowi tetap yakin tetap memang.

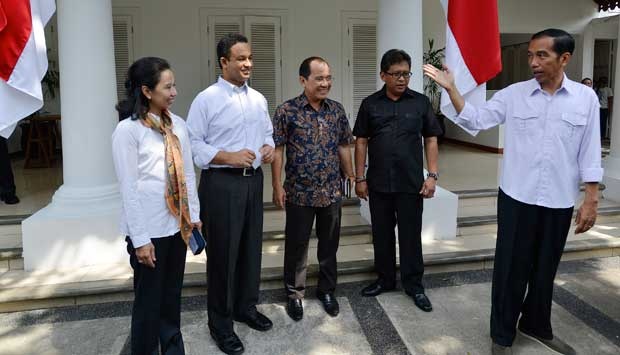

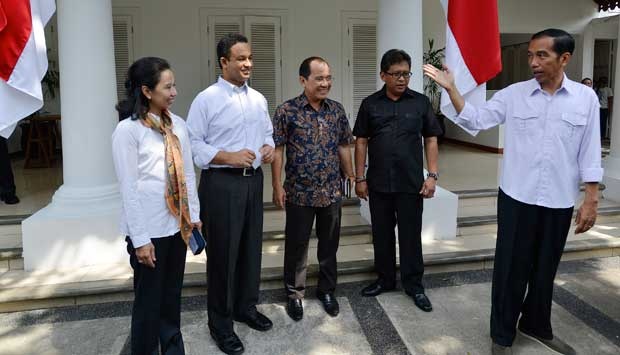

Tim Transisi Jokowi (Tempo.co)

Salah satu gerak cepat yang dilakukan Jokowi adalah membentuk tim transisi pemerintahan. Tim transisi ini ditugaskan untuk melakukan koordinasi dengan pemerintahan SBY yang akan segera digantikannya, serta menjalankan tugas-tugas lainnya sehingga begitu dia dilantik sebagai presiden, langsung sudah bisa tancap gas bekerja memulai jabatan Presidennya.

Seperti yang dilakukan ketika menjadi Walikota Solo dan Gubernur DKI Jakarta, Jokowi bersama JK juga telah berkomitmen untuk mengubah dan menciptakan sistem-sistem baru di dalam pemerintahannya sedemikian rupa sehingga benar-benar tercipta efesiensi dan efektifitas kerja yang maksimal dalam melayani rakyat, memperkecil sekecil-kecilnya kesempatan melakukan KKN oleh semua aparatur negara (dengan mengandalkan kemajuan sistem teknologi dan informasi, sistem perektrutan, dan lain-lain), memilih dan menentukan menteri-menteri yang tidak terikat dengan partai politik mana pun, menteri-menterinya harus mereka yang tidak merangkap jabatannya di partai politiknya, tetapi yang didasarkan pada kriteria profesionalisme yang obyektif, melibatkan masukkan dari masyarakat, dan lain sebagainya.

Terpilihnya Jokowi sebagai presiden juga tidak disukai para politikus dan pejabat negara koruptor, kaum kapitalis yang selama ini besar dengan mengandalkan KKN, para mafia korporasi raksasa, serta kelompok-kelompok radikal dan sektarian agama.

Selama Pilpres berlangsung berbagai upaya, cara dan daya dilakukan mereka untuk mengagalkan Jokowi ke kursi presiden. Kekuatan penuh dikerahkan, tenaga, daya, dan dana dicurahkan habis-habisan, cara haram pun dihalalkan, isu-isu SARA dan fitnah-fitnah keji pun dilakukan, tetapi tetap saja gagal. Sepertinya hanya tinggal satu cara saja yang belum mereka lakukan, yang mudah-mudahan saja tak akan pernah mereka coba lakukan, yaitu usaha pembunuhan terhadap Jokowi, sebagaimana terhadap Fernando Lugo dua hari menjelang dia dilantik itu.

Tetapi, upaya-upaya untuk menjegal Jokowi pasti tidak akan berhenti sampai di sini saja. Hampir pasti selama Jokowi berkuasa nanti pun dia akan tetap diganggu dengan berbagai cara dan intrik-intrik politik, termasuk oleh koalisi-koalisi oposisi di parlemen. Mereka pasti akan terus mencari-cari kesalahan Jokowi untuk dijadikan alasan menjatuhkannya di tengah jalan. Seperti yang dialami oleh Fernando Lugo, yang akhirnya berhasil dilengserkan hanya setahun menjelang masa jabatan resminya berakhir. Atau, seperti yang pernah dilakukan kelompok Poros Tengah pimpinan Amien Rais terhadap Gus Dur.

Jokowi bukan tidak menyadari hal ini, oleh karena itu dia beberapakali menyatakan secara terang-terangan, meminta dukungan sepenuhnya dari seluruh rakyat untuk bersama-sama melawan kelompok-kelompok tersebut. Dengan pengawasan ketat dan bersatunya rakyat dalam mendukung pemerintahan Jokowi – selama dia berada di jalur yang benar, niscahya apapun kekuatan jahat yang mencoba menjegalnya secara ilegal dipastikan akan menemukan kegagalan.

Selain itu tentu saja diharapkan dukungan sepenuhnya dari segenap parpol koalisi yang mendukung Jokowi-JK, termasuk komitmen penuh JK sendiri, agar tetap setia dan sadar sepenuhnya bahwa meskipun dia lebih senior dan berpengalaman daripada Jokowi, dia tetap adalah bawahannya Jokowi, dengan mematuhi apa saja yang telah digariskan atau diprogramkan Jokowi dalam kedudukannya sebagai Presiden.Berbeda pendapat boleh saja dan itu wajar, asalkan janganlah sampai terlalu menonjol, dan mengganggu efektifitas kerja pemerintahan mereka.

Jangan sampai sejarah Fernado Lugo di Paraguay terulang pada Jokowi di Indonesia.

Semoga. Amin. ***

Daftar Pustaka:

- Anak-anak Revolusi Jilid 2, Gramedia, 2014, oleh Budiman Sudjatmiko

- Wikipedia

Jokowi’s Challenge – Part 1: The timely rise of a furniture salesman?

http://asiancorrespondent.com/125856/jokowis-challenge-part-1-the-timely-rise-of-a-furniture-salesman/

Patrick Tibke

Patrick Tibke

Despite having been involved in politics for little more than nine years, Joko ‘Jokowi’ Widodo has already contested four separate elections – all of which he won – and is now poised to become president of the world’s third largest democracy. What does this rather anomalous statistic tell us about the rise to power of a man who has gone from small-town furniture salesman to leader of a vast archipelagic nation in less than a decade? Has Jokowi’s presidency arrived prematurely, and if so, how did it come to pass?

We know that Jokowi is a political outsider; someone who has fought for power from the grassroots up and beaten many of the nation’s established elites on their own turf. This is, indeed, a highly symbolic victory for Jokowi, as well as an important milestone for Indonesia’s young democracy, but how was such a feat achieved by a man with absolutely no experience in national level politics?

Jokowi was a late choice as presidential candidate for the PDI-P party, having been thrust into the contest for lack of any other conceivable option by the domineering and monolithic chairlady of the party, Megawati Soekarnoputri. The 67-year-old Megawati, daughter of Indonesia’s founding father Soekarno, has fought and lost two previous presidential elections on the PDI-P ticket, and probably would have done the same this year if it wasn’t for the fanatical popularity of Joko Widodo. Jokowi was less than two years into his first term as Jakarta governor when he finally received Megawati’s last-minute “blessing” and was nominated for the presidential ticket, a responsibility which he willingly accepted but had never demanded of his own volition.

Although the long delay in putting forward Jokowi’s candidacy hindered his campaign from the outset, his bid for presidency was backed by hugely popular demand – and his victory at first seemed a foregone conclusion. In his short time as Jakarta governor, Jokowi had already cultivated an indelible persona as a down to earth, reformist politician, renowned for his love of wearing chequered shirts as much as his willingness to visit poor constituents and chat with them on their terms. This was a winning formula for Jokowi in both his native Solo and Jakarta, and he had become a media sensation long before being coaxed towards the State Palace by Megawati.

In the early days of his head-to-head battle with Prabowo Subianto for the presidency, Jokowi was forecast to win the election by a margin of perhaps 30 percent, but events along the campaign trail quickly revealed serious shortcomings in Jokowi’s suitability for presidency. In public appearances Jokowi often seemed uninspired, unprepared and excessively self-deprecating. His oratory was lacklustre, he seemed to lack big ideas, and he sometimes committed the bizarre error of pointing out that he is “a simple person; not [a] smart” man, as if to imply that any old administrator with a fondness for straightforward solutions and clean governance could do a decent job as president of the world’s fourth most populous country.

Indeed, it was exactly this sort of humble and approachable comportment which made Jokowi an effective and compelling politician among poor voters at the municipal level, but the everyman charm inevitably seemed underwhelming coming from an aspiring president. This contradiction has now become an antinomy bind for Jokowi, which he will either have to accept as permanent or learn to outgrow once in power. The latter option will be all the more difficult, however, given that Jokowi has been offered little room for autonomy by his party superiors, particularly Megawati, who sees Jokowi merely as a subservient functionary tasked with “implementing the party’s ideology.”

In contrast to Jokowi’s humility, Prabowo proved to be a formidable opponent precisely because of his appetite for bluster and self-conviction, even though his campaign relied heavily on clichéd, antagonistic narratives, such as foreign crooks pilfering the great wealth of Indonesia, or a supine class of squabbling politicians presiding over a “destructive democracy.” Admittedly, Prabowo’s campaign also benefitted enormously from the smear tactics employed by his supporters, who ‘accused’ Jokowi of being a closet Christian, of Chinese descent, Singaporean birth, and a sympathiser of Indonesia’s long deceased communist party, the PKI. By the end of the election, team Prabowo had thrown almost every trick in the book at poor Jokowi. But perhaps even more revealingly, it also has to be said that Jokowi did not do nearly enough to defend himself or hit back at Prabowo’s own, genuine weak points.

Why, for instance, did Jokowi never challenge Prabowo to account for his abysmal human rights record – which includes allegations of torture, kidnap, disappearance and mass murder. Prabowo has never stood trial for any of these violations, despite huge amounts of evidence against him and previous recommendations for his prosecution by the National Human Rights Commission. That Jokowi neglected to probe this dark past not only contradicts his own claim to being a human rights defender, but also suggests a timidity of character which certainly doesn’t bode well for his presidency. Additionally, Jokowi should also be criticised for failing to denounce Prabowo’s openly autocratic intentions, such as his support for the termination of ‘costly’ direct presidential elections and a return to Indonesia’s scrapped 1945 Constitution, which would have concentrated yet more power in the office of the executive.

So how is Jokowi expected to play the role of disciplinarian in Indonesia’s top job if he couldn’t even bear to mention his opponent’s most egregious abuses of power, or his obvious fetish for dictatorial politics?

A more combative candidate, if put in Jokowi’s position, would have exploited these weak points and pressured Prabowo to conform – in the spirit of reformasi - to principles of truth, accountability, human rights and greater democracy, which were put in grave danger during this year’s election. Why Jokowi was never more resolute in his defence of these ideals remains an open question, especially so given that his own rise to power would have been utterly inconceivable if it weren’t for the greater openness and democratisation unleashed by Indonesia’s reformasi.

Liberal commentators who recognised these shortcomings in Jokowi’s candidacy were loath to point them out along the campaign trail, knowing that a victory for Prabowo would have been a potential death sentence for Indonesia’s democracy. And thus, despite his obvious lack of experience and subjugation to Megawati, for most liberals Jokowi was always the only credible contender in this year’s election, even before he secured the nomination from his party chair.

So now that Jokowi’s victory is almost a done deal, save for the impudent antics of team Prabowo at the Constitutional Court, we can speak more plainly about the incoming president. Despite the obvious novelty of a furniture salesman-cum-president, the nature of Jokowi’s election victory indicates a faltering of reformasi - both as an ongoing political project and a source of inspiration for Indonesia’s leaders and voters. The very fact that a fugitive like Prabowo was even allowed to compete illustrates how reformasi has so far failed to ensure that well-moneyed, blue-blooded elites can be held accountable for their crimes. And the millions of votes which Prabowo received, despite his pledge to dismantle certain features of Indonesia’s democracy, similarly suggest that the spirit of reformasi is now a spent force among much of the electorate.

On the one hand – with this being so – it is immensely fortuitous that a fundamentally benign and well-meaning politician such as Jokowi was ready and willing to rescue Indonesia’s democracy precisely when required to do so. And in this purely co-incidental sense, Jokowi’s rise to power might be thought of as perfectly timely. However, it goes without saying that Jokowi remains distinctly under-qualified to take up such a pivotal role as president, and he runs the risk of becoming a mouthpiece for more senior and experienced figures around him, such as Megawati and vice president-elect Jusuf Kalla.

In short, Jokowi will have a hard time proving to his supporters that he has not – to borrowa rendering from Edward Aspinall – “already performed perhaps the greatest service he’ll ever perform for his country, and that’s preventing Prabowo from becoming the president.”

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)