King Richard III's Final Moments Were Quick & Brutal

http://www.livescience.com/47869-richard-iii-final-moments-postmortem.html

By Stephanie Pappas, Live Science Contributor

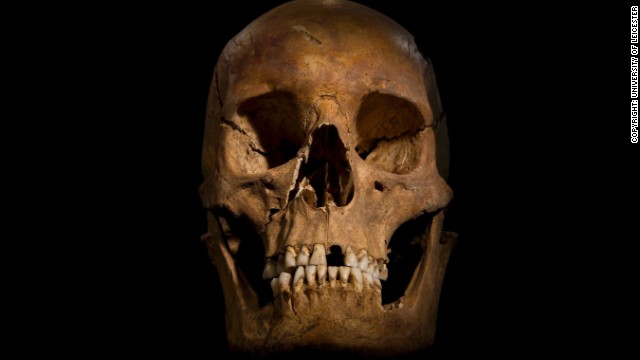

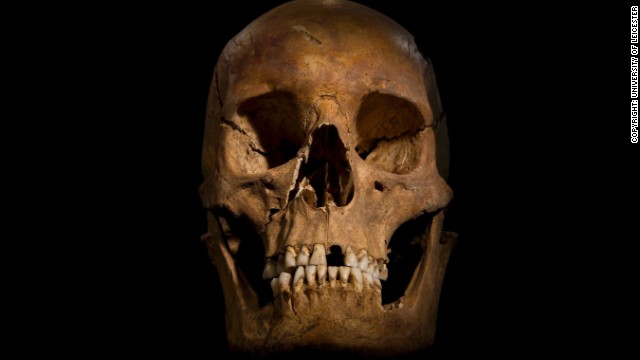

A photograph of Richard III's jaw and face show penetrating injuries to the maxilla, or upper jaw.Credit: Appleby, et al. Perimortem trauma in King Richard III: a skeletal analysis. The Lancet. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60804-

Credit: by Karl Tate, Infographics Artist

http://edition.cnn.com/2013/02/03/world/europe/richard-iii-search-announcement/index.html?iid=article_sidebar

By Bryony Jones, CNN

Richard III's last moments were likely quick but terrifying, according to a new study of the death wounds of the last king of England to die in battle.

The last king of the Plantagenet dynasty faced his death at the Battle of Bosworth Field on Aug. 22, 1485, only two years after ascending the throne. The battle was the deciding clash in the long-running Wars of the Roses, and ended with the establishment of Henry Tudor as the new English monarch.

But Richard III's last moments were the stuff of legend alone, as the king's body was lost until September 2012, when archaeologists excavated it from under a parking lot in Leicester, England. Now, a very delayed postmortem examination reveals that of nearly a dozen wounds on Richard's body, only two were likely candidates for the fatal blow. Both were delivered to the back of the head. [Gallery: The Search for Richard III's Remains (Photos)]

Battle scars

The initial analysis of Richard III's skeleton highlighted the king's scoliosis and battle scars, including at least eight wounds on the skull. In the new postmortem, detailed today (Sept. 16) in the medical journal The Lancet, scientists took a deeper look, recording 11 injuries on Richard's skeleton that occurred around the time of death, including nine injuries to the skull.

A study of the Medieval king's skeleton reveals traumatic wounds he received at the time of death. (See full infographic)

Credit: by Karl Tate, Infographics Artist

Three of the skull injuries were "shaving injuries" to the top of the head, said study researcher Sarah Hainsworth, a professor of materials and forensic engineering at the University of Leicester. These shallow, glancing blows would have sliced the scalp and shaved the skull bone. They would have bled heavily, but would not have been fatal unless untreated. Notably, patterns of striations in the wounds revealed the same weapon probably created these injuries, Hainsworth told Live Science. [See Images of King Richard III's Battle Injuries]

"If you took a block of cheese into your kitchen and used a serrated blade to cut it, you would see these marks that are characteristic of the blade," she said. Those marks are very similar across the three skull wounds.

But Richard III was almost certainly brought down by more than one man — and more than one weapon. A knife or dagger likely left a 0.4-inch-long (10 millimeters) linear wound on his right lower jaw; he also had a penetrating dagger wound to his right cheek. A keyhole-shaped injury to the top of his head was almost certainly caused by a rondel dagger, a needlelike blade often used in the late Middle Ages. That wound would have caused both internal and external bleeding, but would not have been immediately fatal.

The deathblows likely came from a sword or a bill or halberd, which were bladed weapons on poles often used on the battlefield. At the base of Richard III's skull, researchers found two wounds, one 2.4 by 2.2 inches (60 by 55 mm) and one 1.21 by 0.67 inches (32 by 17 mm). This wound was in line with another, about 4 inches (105 mm) away on the internal wall of the skull, as well as in line with damage to the top vertebrae. In other words, it appears that the blade entered the head, sliced through the brain and hit the opposite side of the skull. [See Infographic of Richard III's Battle Wounds]

The postmortem also revealed two wounds to Richard III's body. One, likely delivered as a blow from behind with a fine-edged dagger, damaged the right 10th rib. Another, a 1.2-inch-long (30 mm) scrape to the pelvis, delivered through the right buttock, had the potential to be fatal. But that wound was almost certainly delivered after death, Hainsworth said, because Richard III was wearing armor on the battlefield that would have protected him.

This CT reconstruction shows how a blade could have entered Richard III's right buttock, scraping the pelvis as it went.

Credit: Appleby, et al. Perimortem trauma in King Richard III: a skeletal analysis. The Lancet. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60804-7

Credit: Appleby, et al. Perimortem trauma in King Richard III: a skeletal analysis. The Lancet. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60804-7

Interpreting trauma on a 500-year-old skeleton is difficult, because soft tissue is missing, Heather Bonney, a human remains researcher at the Natural History Museum, London, who was not involved in the research, said in a statement. However, Bonney said, the findings provide a "compelling account" of Richard III's death.

Last moments

Either of the penetrating head wounds would have been fatal very quickly, Hainsworth said. The findings mesh with near-contemporary accounts of the battle, which hold that Richard III's horse had become mired in mud, forcing him to dismount. He had either removed or lost his helmet, leaving his head and face vulnerable.

"He was surrounded, probably by a number of people with medieval arms," Hainsworth said. "He was a warrior, he was a knight, he was a trained fighter, but he would have seen other people die on the battlefield, so he would be very aware of, if you like, what was in store for him."

The researchers can't say for sure in what order the wounds were delivered, but historical accounts hold that Richard was kneeling with his head bent forward when the fatal wounds were delivered — a tale consistent with the large wounds to the base of the skull. Richard's face was actually less mutilated than many battle casualties of the time, Hainsworth said. The choice to spare his face was likely deliberate, she said, as the victors would want to leave no doubt that it was really Richard they had killed.

After death, Richard's body was stripped of armor and slung over a horse to be taken to Leicester for public display. It was then, Hainsworth said, that the wounds to the back and buttock were likely made as a final humiliation to the defeated king.

"It would have probably been quite quick," Hainsworth said of Richard III's death. "But, I would imagine, nonetheless quite frightening."

King Richard III's bones reveal fatal blows, scientists say

http://edition.cnn.com/2014/09/16/world/europe/richard-iii-bones-injuries/index.html

By Laura Smith-Spark and Val Willingham, CNN

British scientists announced on February 4 that they were convinced "beyond reasonable doubt" that a skeleton found during an archaeological dig in Leicester, England, in August 2012 is that of King Richard III, who was killed at the Battle of Bosworth Field in 1485.

(CNN) -- Richard III was the last English king to lose his life on the battlefield. Scientists who have been testing his remains -- found under a parking lot in the English city of Leicester -- now believe they know how he died.

The 15th-century king was best known to modern Britons as the hunchbacked Shakespearean villain accused of murdering his nephews, the "Princes in the Tower," to usurp the throne.

His life has always been a controversial chapter in English lore. Although he ruled for only two years (1483-85) and died at the age of 32, there has been an ongoing debate over Richard III's portrayal in both English history and English literature.

According to historians, the king's defeat and death at Bosworth Field ended the Wars of the Roses and marked the end of the Middle Ages in England. Though he was a royal, his body was given to local monks, and he was buried in a crude grave in an unknown location.

It was not until archaeologists from the University of Leicester discovered his remains under a parking lot in 2012 that people learned where his body had been buried. Since that time, both scientists and medical researchers have studied the remains to better understand how King Richard III lived and died.

Now, researchers have used modern forensic analysis to reveal that he suffered 11 injuries at or near the time of death, according to a new study published in The Lancet.

Of those, three had the potential to cause death quickly: two to the skull and one to the pelvis. And the scientists believe that the skull injuries were the ones that killed the last monarch from the House of York.

"Richard's injuries represent a sustained attack or an attack by several assailants with weapons from the later medieval period," said Professor Sarah Hainsworth, one of the authors of the study.

"The wounds to the skull suggest that he was not wearing a helmet, and the absence of defensive wounds on his arms and hands indicate that he was otherwise still armored at the time of his death."

The injury to his pelvis might have been inflicted after his death, the team surmised, since the kind of armor that would have been worn by the king in the late 15th century would have protected that area.

"I think the most surprising injury is the one to the pelvis," Hainsworth said. "We believe that this corresponds to contemporary accounts of Richard III being slung over the back of the horse to be taken back to Leicester after the Battle of Bosworth, as this would give someone the correct body position to inflict this injury."

There were nine injuries to the skull in total and two elsewhere on the skeleton.

The team used whole-body CT scans and micro-CT imaging of injured bones to analyze trauma, according to a news release from The Lancet.

They also looked at tool marks on the bones to try to establish what kind of weapons were used.

"The most likely injuries to have caused the king's death are the two to the inferior aspect of the skull -- a large sharp force trauma possibly from a sword or staff weapon, such as a halberd or bill, and a penetrating injury from the tip of an edged weapon," said Professor Guy Rutty, a co-author of the study.

"Richard's head injuries are consistent with some near-contemporary accounts of the battle, which suggest that Richard abandoned his horse after it became stuck in a mire and was killed while fighting his enemies."

Although the findings are interesting to historians, the question remains: Do they change the accounts of King Richard III's last moments in battle? Since none of the wounds overlapped, the researchers were not able to tell in exactly what order they occurred.

"The (investigators) provide a compelling account, giving tantalizing glimpses into the validity of the historic accounts of his death, which were heavily edited by the Tudors in the following 200 years, " said Heather Bonney of the Natural History Museum in London. "I am sure that Richard III will continue to divide opinion fiercely for centuries to come."

After a legal battle, it has been decided that the medieval king will be reburied next spring in Leicester Cathedral, just a stone's throw from where his remains were uncovered.

Scientists at the University of Leicester say their examination of the skeleton shows Richard met a violent death: They found evidence of 11 wounds -- nine to the head and two to the body -- that they believe were inflicted at or around the time of death. Here, the base of the skull shows one of the potentially fatal injuries. This shows clearly how a section of the skull had been sliced off.

The lower jaw shows a cut mark caused by a knife or dagger. The archaeologists say the wounds to Richard's head could have been what killed him.

A wound to the cheek, possibly caused by a square-bladed dagger, can be seen here

This hole in the top of the skull represents a penetrating injury to the top of the head.

Two flaps of bone, related to the penetrating injury to the top of the head, can clearly be seen on the interior of the skull.

The image shows a blade wound to the pelvis, which has penetrated all the way through the bone.

Here, a cut mark on the right rib can be seen.

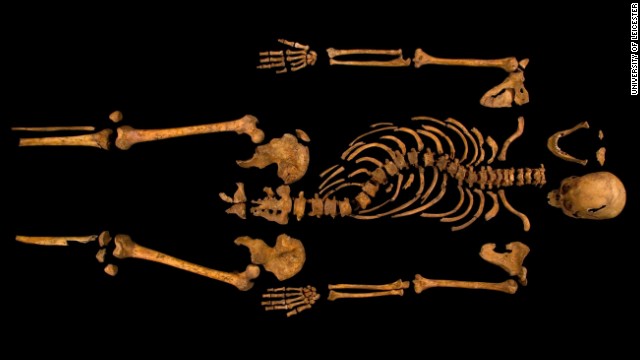

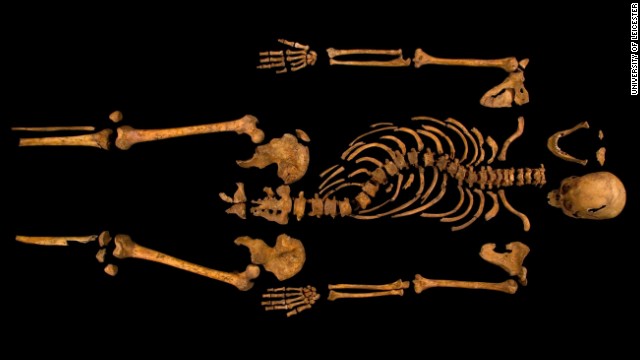

As the skeleton was being excavated, a notable curve in the spine could be seen. (The width of the curve is correct, but the gaps between vertebrae have been increased to prevent damage from them touching one another.)

The body was found in a roughly hewn grave that experts say was too small for the body, forcing it to be squeezed into an unusual position. The positioning also shows that his hands may have been tied.

Who was Richard III?

Richard III was the last Plantagenet king of England, and the last English king to die in battle.

Born on October 2, 1452, he grew up during the bitter and bloody Wars of the Roses, which pitted two aristocratic dynasties, the House of York and the House of Lancaster, against each other in a fight for the throne.

The wars, which took their name from the families' symbols, a red rose for Lancaster and a white rose for York, were fought between 1455 and 1485.

While Richard was still a child, they led to the deaths of his father, the Duke of York, and his brother Edmund, and forced him into exile.

As the youngest son, Richard was never expected to become king, and instead spent many years as a nobleman, apparently intent on founding his own dynasty. His brother Edward became king in 1461, and Richard proved a loyal supporter.

"Shakespeare paints a picture of Richard as a scheming, plotting villain always aiming for the throne, but if that was the case, why didn't he kill the king?" says historian John Ashdown Hill, author of "The Last Days of Richard III."

"That would have been the easiest way, but he served his brother loyally for over 20 years."

When Edward IV died unexpectedly in 1483, he was succeeded by his 12-year-old son, Edward V, with Richard as his protector.

Within weeks, however, parliament had declared the boy illegitimate, and installed Richard as king in his place.

Edward and his brother were held in the Tower of London, and later disappeared. Richard has long been blamed for their murder.

Richard III was the last Plantagenet king of England, and the last English king to die in battle.

Born on October 2, 1452, he grew up during the bitter and bloody Wars of the Roses, which pitted two aristocratic dynasties, the House of York and the House of Lancaster, against each other in a fight for the throne.

The wars, which took their name from the families' symbols, a red rose for Lancaster and a white rose for York, were fought between 1455 and 1485.

While Richard was still a child, they led to the deaths of his father, the Duke of York, and his brother Edmund, and forced him into exile.

As the youngest son, Richard was never expected to become king, and instead spent many years as a nobleman, apparently intent on founding his own dynasty. His brother Edward became king in 1461, and Richard proved a loyal supporter.

"Shakespeare paints a picture of Richard as a scheming, plotting villain always aiming for the throne, but if that was the case, why didn't he kill the king?" says historian John Ashdown Hill, author of "The Last Days of Richard III."

"That would have been the easiest way, but he served his brother loyally for over 20 years."

When Edward IV died unexpectedly in 1483, he was succeeded by his 12-year-old son, Edward V, with Richard as his protector.

Within weeks, however, parliament had declared the boy illegitimate, and installed Richard as king in his place.

Edward and his brother were held in the Tower of London, and later disappeared. Richard has long been blamed for their murder.

Richard III: The mystery of the king and the car parking lot

http://edition.cnn.com/2013/02/01/world/europe/search-for-richard-iii/index.html?iid=article_sidebar

By Bryony Jones, CNN

Leicester, England (CNN) -- The line snakes around the block, hundreds of people wrapped up against the early autumn chill. The crowd waits patiently as a sensibly-dressed, middle-aged woman wanders along the queue, handing out flyers and apologizing for the delay.

"He's been waiting hundreds of years," says one woman, gesturing towards the archway up ahead with a smile. "It won't kill us to hang on for half an hour."

"He" is Richard III, one of the most famous kings of England, remembered by school children and Shakespeare aficionados alike as a notorious villain, hunchbacked and hateful, accused of killing his own nephews, the "Princes in the Tower," to usurp the throne, and whose whereabouts were, until recently, a complete mystery.

The history books record that in August 1485, Richard - the last English king to die in battle - rode out from Leicester, in central England, to the Battle of Bosworth Field. There he met his end; his body was returned to the city days later, ignominiously lashed to a packhorse.

While other monarchs might have been granted all the pomp and ceremony of a state funeral, as a defeated warrior, Richard was accorded no such regal treatment. Instead his naked remains were put on display to prove to supporters and opponents alike that he really was dead, before being hastily buried in a nearby church.

Which is why, more than 520 years on, a crowd has gathered in this municipal car park, though there's little to explain their excitement - at first glance, the most remarkable thing seems to be the lack of vehicles in the worn white parking bays.

Overlooked by the spire of the nearby cathedral, fluorescent overall-clad archaeologists and historians gather near a hole in the ground. It looks like any other set of roadworks, the surface scraped back to reveal layers of earth.

Remains matching the description of Richard III were found buried beneath a parking lot in the English city of Leicester last year

But at the far end of the trench, a laminated copy of a priceless portrait offers a hint as to why so many people have chosen to spend their Saturday morning in a parking lot: Experts believe this uninspiring gray square of tarmac was once part of the Greyfriars Friary -- and might, therefore, be the last resting place of Richard III.

Some of them weren't so sure at first, however. "It seemed like such a harebrained scheme," Richard Buckley, the lead archaeologist on the project, tells CNN. "We didn't expect to find anything."

Applying for permission to dig at the site, and potentially exhume a body, or bodies, Buckley says he wrote: "In the unlikely event that we find the remains of Richard III..."

Nonetheless, at the tail end of last summer, a team of experts dug three trenches across the site and began hunting for evidence of the long-lost friary, where Richard III was recorded to have been buried.

The search turned up traces of the building, and then something altogether more exciting: A human skeleton, complete with evidence of battle wounds -- a blow to the head, and an arrow in the back -- and scoliosis, or curvature of the spine.

"I didn't think it was likely to be him at first," explains bioarchaeologist Jo Appleby, who excavated the remains. "The skull didn't seem to be in quite the right place -- now we know that's because of the scoliosis -- but it didn't seem to 'go' with the legs.

"When I lifted the skull and saw the injury, a little alarm bell started to ring, but I told myself perhaps someone had dug into the grave at a later date and hit it with a spade, so I thought 'Don't say anything yet.'

"I cleared the arms and legs, and then went up the spine, hunting for vertebrae, [but] they weren't there, they weren't where I expected them to be. Instead they went in completely the wrong direction. At that point, I thought 'Hang on!'"

"Someone came over and said 'I think you need to see this,'" Buckley says. "We were looking at something else, so I said 'I'm a bit busy at the moment,' and they said 'No, no, you really need to see this.'"

They were stunned to discover the remains were in surprisingly good condition - particularly given the fact they were apparently laid to rest in a simple shroud, with no coffin to protect them.

"There have been so many changes to the site over the years that the chances of finding the remains were so slim," says local historian David Baldwin. "It wouldn't have been at all surprising had they been destroyed."

As a shiver of anticipation spread across the site, one figure sat, deathly pale and shaking, at the side of the trench.

Philippa Langley had spent years trying to convince archaeologists and authorities alike to allow the dig for Richard III to go ahead. Now she watched, in shock, as the search she had championed for so long reached its climax.

"It's been a real labor of love," she told CNN. "Three years of hard work and tough graft, of people saying we'd never find him, but it looks like it may have paid off."

Langley, a screenwriter, became intrigued by Richard III after reading a book about him on holiday, and quickly decided he would make a perfect subject for a film.

"His story absolutely blew me away," she says. "I asked myself 'Why has nobody written this? Why has nobody told this guy's story?' Robin Hood has had his moment in the cinema, now it's time for Richard III to have his time on the big screen too.

"I decided I needed to do some research -- I needed to know who he was, what he was about, I needed to get inside his head, talk his talk, walk his walk, so I went to Leicester and to Bosworth, but I felt there was no fitting conclusion to the story."

So she decided to help create one, by forcing historians to look again at his story, to find "the real man, and not the myth," because, she believes: "With the truth, he'll finally be able to rest in peace."

Langley hopes the physical evidence found so far will be enough to make people rethink their image of Richard III as a caricature villain.

"It disproves the Tudor writers who claimed terrible things about him: That he was hunchbacked, that he was two years in the womb, that he was born with hair and teeth," she says.

"Instead we can see that he was a strong, capable man, and it blows all those misconceptions away. It gives us so much information about Richard, the real Richard, before the Tudor writers got to him.

"I'm not looking for a saint, but a real man -- if I've got to portray him on a big screen I want to show the real him. He wasn't always great and good, but that's fine, if he was, we'd all be bored to death."

Michael Ibsen, a Canadian-born cabinetmaker, is a potential DNA match for Richard III

She has even been in talks with

Leicestershire lad turned Hollywood hero Richard Armitage -- last seen as Thorin Oakenshield in "The Hobbit"

-- to play the king.

"He was born to play the

role," she explains. "He's an amazing doppelganger for Richard III,

he was born a couple of miles from Bosworth on the anniversary of Richard's

death, and he was even named after him."

The film won't be the first

attempt to rehabilitate Richard III in the eyes of the general public - mystery

writer Josephine Tey tried it in the 1950s with "The Daughter of Time,"

in which her detective hero "discovers" the truth about the

much-maligned monarch.

It was this book which first

sparked the curiosity of Michael Ibsen, prompting him to rethink the image he

had grown up with, of Richard III as "this evil figure who killed the

Princes in the Tower."

Now the Canadian-born

cabinetmaker finds himself at the heart of the story, with a role he could

never have imagined when he read Tey's novel 20 years ago: The potential DNA

match for a long-dead king of England.

"Of course, I'd rather be

related to a benign king figure than a brutal murderer, so it's hard not to be

biased, but some of the history is so vitriolic, I'm a little suspicious -- can

he really have been that bad?"

Historian John Ashdown Hill,

author of "The Last Days of Richard III," tracked down Ibsen's

British-born mother Joy in 2004.

"She knew she had an

illustrious family background - they were from the upper class, but had fallen

on hard times -- but she had no idea that this was in her past," Ibsen

says.

Ashdown Hill explained that as a

direct - if long-distant -- female relative of Richard III's sister, Anne of

York, she and her children should have the same mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) as

Richard III.

Joy was skeptical at first, and

in any case, as Ibsen points out "it seemed fairly academic at the time,

we didn't get too excited."

Sadly, Ibsen's mother died before

the Leicester dig could take place, but he was there in her place as work

began, offering up that all important DNA sample.

"My brother and sister and I

all inherited the same mtDNA, but my sister is the only one who can pass it on,

and she has no children, so they caught us just in time," he told CNN,

reflecting on the "surreal experience" of the past few months.

That DNA now has "the

potential to change history," according to Lin Foxhall, professor of

archaeology at the University of Leicester.

Experts speaking ahead of

Monday's announcement expressed hope that the DNA sample might also reveal

other physical traits of Richard III.

"It depends how much DNA we

are able to extract," said Turi King, the scientist carrying out those

all-important tests. "The more we get, the more specific we can be."

"If enough DNA is collected,

we might even be able to tell hair color, eye color," said Foxhall, adding

that this, together with facial reconstruction would be an "interesting

test. since we have portraits of Richard III, but like written histories, they

too can be biased and polemical."

Ashdown Hill, who has spent more

than 10 years investigating the story of Richard III, is at pains to point out

that the key piece of evidence he helped track down may not be the be-all and

end-all of the story.

"DNA is important, but it's

not the only thing, and even if it does match, there will always be some people

who say 'It's not him,'" he says. "There's no label on the bones, and

there's no-one alive who can say 'I knew him, that's him.'"

"It's always going to be a

leap of faith. All we can do is stack up as much evidence as we can, so that

leap is as small as possible, but in the end, there has to be an element of

belief."

Yet for him, the question was

answered in a "very strange moment" at the end of that long day last

August.

"A white van was brought

into the car park to take the remains away, and I was asked to carry the box to

the van," he says. "I had all sorts of thoughts going through my

head: This was Richard III, I had been looking for him for so long, and there I

was, as close to him as it is possible to be."

Where does skeleton revelation leave legend of Richard III?

http://edition.cnn.com/2013/02/04/opinion/richard-iii-phil-stone-oped/index.html?iid=article_sidebar

By Dr Phil Stone

Editor's note: Dr. Phil Stone is a radiologist and the chairman of theRichard III

Society. He frequently lectures on behalf of the society and is a

contributor to its in-house magazine, the Ricardian Bulletin.

(CNN) -- We can

assume that when Richard III was interred by the monks in the church of the

Greyfriars, possibly with a few of Henry Tudor's henchmen present to see that

it was done, it would not have been the burial a king of England could have

expected.

Theconfirmation that the remains

found in Leicester are those of King Richard means that, at last, this can be put

right and he can be laid to rest with the solemnity and dignity that is

appropriate for an anointed king.

Even more significantly, the

finding and reinterment of Richard III's remains will, we hope, open up the

debate about the king and his reputation. It would make such a difference if

people would start to look into the history of this much maligned monarch without

the old prejudices. Perhaps, then, they will see past the myth and innuendo

that has blackened his name and find the truth. No one is going to suggest that

he was a saint - I have said on many occasions that we are not the Richard III

Adoration Society - but even a cursory reading of the known facts will show

that the Tudor representation of Richard III, especially that in Shakespeare's

well known play, just doesn't stand up.

Shakespeare wrote a great play

but even he must have been aware that he was twisting the facts in order to

make it more dramatic. After all, he called it a "tragedy" not a

"history." His Richard III is a villain and a superb villain at that,

but Shakespeare was not writing history, no matter what the Duke of Marlborough

might have thought. There are many instances where the portrayal just does not

fit the historical record. For instance, in one of his three plays about Henry

VI, Shakespeare has Richard of Gloucester, later Richard III, killing the Duke

of Somerset at the first battle of St Albans. At the time of that fight,

Richard Plantagenet wasn't Duke of Gloucester and, more cogently, he wasn't yet

three years old!

The Richard III Society was

founded as the Fellowship of the White Boar almost 90 years ago. It was

re-founded in 1956 and changed its name three years later, as a result of

which, it took on a more missionary approach to its aims of securing a

reassessment of the material relating to the life and times of this king. This

was not new, of course, as reassessment had begun in the 17th century after the

death of the last Tudor monarch and it has continued ever since. Over the

centuries, the approach to Richard III's reputation has swung like a pendulum.

If, as a result of the finding of

Richard III and all the publicity it has engendered, people can be encouraged

to read the facts for themselves, it will be a truly great event and all who

have been involved in the project are to be congratulated. I have followed its

progress from an early stage when Philippa Langley, a member of the Richard III

Society whose idea it was, first came to me to ask if she thought it was viable

and would the society be willing to back it. I have tried to encourage her at

times when doors were being shut and when there were setbacks and together we

appealed for money when there was a shortfall. It is a great testament to

Philippa's tenacity and bloody-mindedness that the project has been so

successful.

Richard III was no saint but

neither was he a criminal. All but one of the so-called crimes laid at his door

can be refuted by the facts. The one that cannot is the disappearance of his

nephews, the "Princes in the Tower" and the answer to that question

is simply that no-one knows what happened to them. All that follows is

conjecture - they just disappeared.

Richard had no need to kill them; they had

been declared bastards. Henry VII needed them out of the way, but he got so

scared whenever a pretender appeared that it is likely that he knew they were

alive at the time Richard died at Bosworth. Did they die in 1483 or 1485 or

were they spirited out of the country to their aunt, the Dowager Duchess of

Burgundy? We will probably never know.

To return to the question of what

will the finding of Richard III's remains mean? Let us hope it means more clear

thinking, a wider debate, greater seeking of the truth and above all, may it

set the record straight for Good King Richard!

Body found under parking lot is King Richard III, scientists prove

Leicester, England (CNN) -- DNA tests have confirmed that human remains found buried

beneath an English car park are those of the country's King Richard III.

British scientists announced Monday they are convinced "beyond

reasonable doubt" that a skeleton found during an archaeological dig in

Leicester, central England, last August is that of the former king, who was

killed at the Battle of Bosworth Field in 1485.

Mitochondrial DNA extracted from

the bones was matched to Michael Ibsen, a Canadian cabinetmaker and direct

descendant of Richard III's sister, Anne of York, and a second distant

relative, who wishes to remain anonymous.

Experts say other evidence --

including battle wounds and signs of scoliosis, or curvature of the spine --

found during the search and the more than four months of tests since strongly

support the DNA findings -- and suggest that history's view of the king as a

hunchbacked villain may have to be rewritten.

Ibsen said he reacted with

"stunned silence" when told the closely-guarded results. "I

never thought I'd be a match, and certainly not that it would be so close, but

the results look like a carbon copy," he told reporters.

The skeleton was discovered

buried among the remains of what was once the city's Greyfriars friary. After

centuries of demolition and rebuilding work, the grave's exact location had

been lost to history, and there were even reports that the defeated monarch's

body had been dug up and thrown into a nearby river.

The remains will be reburied in

Leicester Cathedral, close to the site of his original grave, once the full

analysis of the bones is completed.

Richard III's body was found in a

roughly-hewn grave, which experts say was too small for the body, forcing it to

be squeezed in to an unusual position.

Its feet had been lost at some

point in the intervening five centuries, but the rest of the bones were in good

condition, which archaeologists and historians say was incredibly lucky, given

how close later building work came to them -- brick foundations ran alongside

part of the trench, within inches of the body.

What was initially thought to be

a barbed arrowhead found among the dead king's vertebrae turned out instead to

be a Roman nail, disturbed from an earlier level of excavation.

Archaeologists say their

examination of the skeleton shows Richard met a violent death: They found

evidence of 10 wounds -- eight to the head and two to the body -- which they

believe were inflicted at or around the time of death.

"The skull was in good

condition, although fragile, and was able to give us detailed

information," said bioarchaeologist Jo Appleby, who led the exhumation of

the remains last year.

The king had suffered two severe

blows to the head, either of which would have been fatal, according to Appleby.

The injuries suggest that he had lost his helmet in the course of his last

bloody battle.

Appleby said there were also

signs that Richard's corpse was mistreated after his death, with evidence of

several "humiliation injuries," which fitted in with historical

records of the body being displayed, naked, in Leicester before being laid to

rest.

Richard Buckley, the lead

archaeologist on the project said the unusual position of the skeleton's arms and

hands suggested he may have been buried with his hands tied.

Investigators from the University

of Leicester had been examining the remains for months.

Others got their first glimpse of

the battle-scarred skull that may have once worn the English crown early Monday

when the university released a photograph ahead of its announcement.

Turi King, who carried out the

DNA analysis, said it was a "real relief" when the results came

through.

"I went really quiet. I was

seeing all these matches coming back, thinking, 'That's a match, and that's a

match, and that's a match.' At that point I did a little dance around the

lab."

King pointed out that "in a

generation's time, the DNA match would not have been possible, since both

individuals used in the tests are the last of their line," a fact echoed

by Ibsen, who told CNN before the results came through that "they caught

us just in time."

The initial discovery of the

remains provoked much debate in Britain as to what would happen with the body,

if it were proven to be that of Richard III, with many calling for a state

funeral at Westminster Abbey, and others backing a burial in York Minster, in

keeping with the king's heritage as a member of the House of York.

But on Monday those involved in

the search said he would be reinterred in Leicester

Cathedral, the closest

church to the original grave site in a memorial service expected to be held

early next year.

Canon Chancellor David Monteith

said it was important to remember that as well as being the subject of

important historical and scientific research, the skeleton also represented

"the mortal remains of a person, an annointed Christian king," and as

such should be treated with dignity.

Supporters of the infamous king,

including members of the Richard III Society, hope the discovery will now force

academics to re-examine history, which they say has been tainted by

exaggerations and false claims about Richard III since the Tudor era.

Screenwriter Philippa Langley,

who championed the search for several years, told CNN she wanted "the

establishment to look again at his story," saying she wanted to uncover

the truth about "the real Richard, before the Tudor writers got to

him."

"This has been an

extraordinary journey of discovery," Langley said. "We came with a

dream and today that dream has been realized. This is an historic moment that

will rewrite the history books."

Richard still the criminal king

http://edition.cnn.com/2013/02/04/opinion/jones-richard-third/index.html?iid=article_sidebar

By Dan Jones

Editor's note: Dan Jones is a historian and newspaper columnist based in London.

His new book, "The

Plantagenets" (Viking),

is published in the U.S. this spring. Follow him on Twitter.

(CNN) -- Richard

III is the king we British just can't seem to make our minds up about.

The monarch who reigned from 1483

to 1485 became, a century later, the blackest villain of Shakespeare's history

plays. The three most commonly known facts of his life are that he stole the

crown, murdered his nephews and died wailing for a horse at the Battle of

Bosworth in 1485. His death ushered in the Tudor dynasty, so Richard often

suffers the dual ignominy of being named the last "medieval" king of

England -- in which medieval is not held to be a good thing.

Like any black legend, much of it

is slander.

Richard did indeed usurp the

crown and lose at Bosworth. He probably had his nephews killed, too; it is

unknowable but overwhelmingly likely. Yet as his many supporters have been busy

telling us since it was announced Monday that Richard's lost skeleton was found

in a car park in Leicester, he wasn't all bad. In fact, he was for most of his

life loyal and conscientious.

To fill you in, a news conference

held at the University of Leicester on Monday confirmed what archaeologists

working there have suspected for months: that a skeleton removed from under a

parking lot in the city center last fall was indeed the long-lost remains of Richard III.

His official burial place --

under the floor of a church belonging to the monastic order of the Greyfriars

-- had been lost during the dissolution of the monasteries that was carried out

in the 1530s under Henry VIII. A legend grew up that the bones had been thrown

in a river. Today, we know they were not.

What do the bones tell us?

Well, they show that Richard --

identified by mitochondrial DNA tests against a Canadian descendant of his

sister, Anne of York -- was about 5-foot-8, suffered curvature of the spine and

had delicate limbs. He had been buried roughly and unceremoniously in a shallow

grave too small for him, beneath the choir of the church.

He had died from a slicing blow

to the back of the head sustained during battle and had suffered many other

"humiliation injuries" after his death, including having a knife or

dagger plunged into his hind parts. His hands may have been tied at his burial.

In other words, we have quite a

lot of either new or confirmed biographical information about Richard.

He was not a hunchback, but he

was spindly and warped. He died unhorsed. He was buried where it was said he

was buried. He very likely was, as one source had said, carried roughly across

a horse's back from the battlefield where he died to Leicester, stripped naked

and abused all the way.

All this is known today thanks to

a superb piece of historical teamwork.

The interdisciplinary team at

Leicester that worked toward Monday's revelations deserves huge plaudits. From

the desk-based research that pinpointed the spot to dig, to the digging itself,

to the bone analysis, the DNA work and the genealogy that identified Richard's

descendants, all of it is worthy of the highest praise. Hat-tips, too, to the

Richard III Society, as well as Leicester's City Council, which pulled together

to make the project happen and also to publicize the society and city so

effectively.

However, should anyone today tell

you that Richard's skeleton somehow vindicates his historical reputation, you

may tell them they are talking horsefeathers.

Richard III got a rep for a

reason. He usurped the crown from a 12-year old boy, who later died.

This was his great crime, and

there is no point denying it. It is true that before this crime, Richard was a

conspicuously loyal lieutenant to the boy's father, his own brother, King

Edward IV. It is also true that once he was king, Richard made a great effort

to promote justice to the poor and needy, stabilize royal finances and contain

public disorder.

But this does not mitigate that

he stole the crown, justifying it after the fact with the claim that his

nephews were illegitimate. Likewise, it remains indisputably true that his

usurpation threw English politics, painstakingly restored to some order in the

12 years before his crime, into a turmoil from which it did not fully recover

for another two decades.

So the discovery of Richard's

bones is exciting. But it does not tell us anything to justify changing the

current historical view of Richard: that the Tudor historians and

propagandists, culminating with Shakespeare, may have exaggerated his physical

deformities and the horrors of Richard's character, but he remains a criminal

king whose actions wrought havoc on his realm.

Unfortunately, we don't all want

to hear that. Richard remains the only king with a society devoted to

rehabilitating his name, and it is a trait of some "Ricardians" to refuse

to acknowledge any criticism of their hero whatever. So despite today's

discovery, we Brits are likely to remain split on Richard down the old lines:

murdering, crook-backed, dissembling Shakespearean monster versus

misunderstood, loyal, enlightened, slandered hero.

Which is the truth?

Somewhere in between. That's a

classic historian's answer, isn't it? But it's also the truth.

King Richard III had worms, scientists say

http://edition.cnn.com/2013/09/04/world/europe/uk-king-richard-worms/index.html?iid=article_sidebar

By Dana Ford and Laura Smith-Spark, CNN

London (CNN) -- Even a

king can get them.

Researchers working with the

remains of King Richard III said on Wednesday that he was infected with

roundworms in his intestines.

They know because they found

multiple roundworm eggs in soil samples from around his pelvis, where his

intestines would have been, according to a study published online in the

journal Lancet.

Eggs were not found in a sample

taken from near the king's head, and a sample from around his grave showed only

scant contamination, the researchers said.

Last year, archaeologists

unearthed a body buried beneath a nondescript parking lot in the city of Leicester.

In February, they confirmed the remains were those of Richard III, the last

king of England to die on the battlefield.

The news drew global attention,

thanks in part to Richard's bloodthirsty reputation -- as immportalized in

William Shakespeare's play "Richard III."

As many as 1.2 billion people in

the world are thought to be infected with Ascaris lumbricoides, the kind of

roundworm eggs found in the king's remains, according to the Centers for

Disease Control and Prevention.

Ascaris lives in the intestine

and eggs are passed in the feces.

Some people infected show no

symptoms, but some can have abdominal discomfort. In severe cases, the

infection can cause intestinal blockage and stunt growth in children, the CDC

said.

Cases in present day Britain

are rare, according to the National Health Service, with most cases

now diagnosed occurring in people who have traveled from parts of the world

where roundworm is present.

War of the

Roses

King Richard was killed at the

Battle of Bosworth Field in 1485, at age 32. It was the last fight in the War

of the Roses, which ended with Henry VII of the Tudor line on the throne.

The Leicester site is where a

church, known as Greyfriars Friary, once stood.

Over the centuries, the

whereabouts of the friary's remnants were forgotten, but it remained in the

records as the burial place of Richard III.

Last year, archaeologists began

to excavate the parking lot site, and in February announced that they were

convinced "beyond reasonable doubt" that the skeleton found there

belonged to Richard.

Mitochondrial DNA extracted from

the bones was matched to Michael Ibsen, a Canadian cabinetmaker and direct

descendant of Richard III's sister, Anne of York, and a second distant

relative, who wished to remain anonymous.

Experts said other evidence -- including

battle wounds and signs of scoliosis, or curvature of the spine -- found during

the search and more than four months of tests afterward strongly supported the

DNA findings.

The king's remains are due to be

reburied in Leicester Cathedral, close to the site of his original grave, next

year.

Richard III's spine was twisted, not hunched

http://edition.cnn.com/2014/05/29/health/richard-iii-spine-scoliosis/index.html?iid=article_sidebar

By Elizabeth Landau, CNN

(CNN) -- When

Shakespeare wrote of Richard III as a "bunchback'd toad," he didn't

have the benefit of actually seeing the king, who had died in the previous

century.

Now we know the playwright was

probably wrong about Richard's physical features.

Scientists have analyzed the

bones of the British monarch and determined that he was not actually a

hunchback. In fact, he had a significant spinal curve that we would call

scoliosis.

Researchers published their latest results Thursday in the Lancet.

"It's a twist rather than a

forward bend," said study co-author Piers Mitchell of the Department of

Archaeology and Anthropology at the University of Cambridge.

"We were expecting him to

have a hunchback deformity the way Shakespeare described," he added.

Richard III reigned over England

from 1483 to 1485 and died during the two-hour Battle of Bosworth against the

forces of Henry Tudor.

The king's remains were

discovered in 2012 under a parking lot. Archaeologists determined at that time

that Richard III had scoliosis, a condition characterized by a curvature of the

spine.

Researchers wanted to make sure

Richard was like that in life, not just as a result of his bones having been

buried for centuries. Just by looking at his skeleton, they had clues.

"A lot of the bones around

the maximum part of the curve of his scoliosis were asymmetric. One side was

different from the other, which shows that the deformity was a genuine thing

during life."

Using computerized tomography,

researchers created a three-dimensional reconstruction of Richard's spine. They

also made a model of the spine using a 3-D printer. This let them examine the

bones more closely than when the spine was in the ground.

The spine appeared to have a

twist indicative of scoliosis. Researchers measured the angle of curve and used

medical research to understand what Richard's life might have been like.

The diagnosis of scoliosis means

Richard III had a physical health condition in common with about 2% to 3% of

the American population, according to the American Association of Neurological Surgeons.

"Buffy" actress Sarah Michelle Gellar, top golfer Stacy Lewis and

Judy Blume's character Deenie all have it, too.

Richard's scoliosis was probably

not inherited, and it probably began sometime after he was 10, researchers

said.

Conditions such as cerebral palsy

and muscular dystrophy might cause scoliosis, but those are rare explanations, according to the Mayo Clinic.

In up to 85% of people with

scoliosis, including Richard III, there is no known cause, according to the National Institutes of Health. Doctors call this

"idiopathic." Normally in scoliosis, the spine takes on a shape that

resembles the letter "S" or "C."

Children may be prescribed a

brace to prevent further curving. The NIH says patients who are still growing

and have curves of more than 25 to 30 degrees, or a curve between 20 to 29

degrees that is getting worse, will be advised to wear a brace.

Richard's spine has a curvature

of 70 to 80 degrees. Anything over 50 degrees is a candidate for surgery,

Mitchell said; the NIH puts this figure at 45 degrees.

Research has not proved that

chiropractic manipulation, electrical stimulation, nutritional supplementation

or exercise stop curves that are worsening, although exercise has other

benefits for general well-being.

The spinal curve probably

wouldn't have reduced Richard's lung capacity such that he couldn't exercise,

researchers said.

There are other discrepancies

between Shakespeare's descriptions and the skeleton besides the back problem,

Mitchell said.

The real Richard does not appear

to have had a limp or a withered arm, as Shakespeare had described. His trunk

and abdomen would have appeared short compared with his arms and legs, Mitchell

said. His right shoulder would have been slightly higher than the left.

His curved spine and these other

asymmetries would have been more obvious when the king was unclothed than

clothed.

"However, a good tailor and

custom-made armour could have minimized the visual impact of this," the

study's authors wrote.

Richard III's bones reveal king's taste for luxury food and wine

http://edition.cnn.com/2014/08/18/world/europe/richard-iii-bones-reveal-luxury-lifestyle/index.html

By Bryony Jones, CNN

(CNN) -- Tests on the long-lost skeleton of Richard III reveal the

medieval monarch had a taste for rich foods such as peacock, heron and swan,

and that his liking for the finer things in life -- including wine -- increased

significantly after he became the king of England.

Scientists at the British Geological Survey measured the levels of

isotopes including oxygen, strontium, nitrogen and carbon in the remains of

Richard III, found buried beneath a parking lot in the English city of

Leicester in 2012.

In a paper published in the Journal of Archaeological Sciences,

they say the tests can reveal clues as to where a person lived, and what they

ate and drank, allowing experts "to reconstruct the life history" of

the last Plantagenet king.

Isotope geochemist Angela Lamb,

who led the study, said two teeth -- a molar and premolar -- and two bones -- a

rib and femur -- were analyzed because each held different information and

could offer a variety of clues to Richard III's life.

"The teeth develop in

childhood and don't change, so from them we can get information about a

person's early years," she told CNN.

"Bones are different; they

remodel and repair themselves through life -- if you break a bone, for example,

it can heal. The femur is dense and slow-growing, so it can tell us about the

last 10 to 15 years of a person's life, whereas the rib bone is much more

spongy and regenerates much more quickly, so it can reveal information about

the last two to three years."

High-protein

diet

This is key in the case of

Richard III, since he became king just 26 months before his death at the Battle

of Bosworth in 1485 -- and analysis suggests his diet changed markedly in the

few short years after he was crowned.

Medieval aristocrats are known to

have eaten high-protein diets full of freshwater fish and wildfowl, in part

because of religious observances that called for "meat-free" fasting

for up to a third of the year. Fish and wildfowl -- birds such as heron, swan

and egret -- were not considered meat.

"Obviously, Richard was a

nobleman beforehand, and so his diet would be reasonably rich already,"

explained Lamb. "But once he became king we would expect him to be wining

and dining more, banqueting more. Food was a real mark of status in the medieval

period.

"We have the menu from his

coronation banquet and it was very elaborate -- lots of wildfowl, including

real 'delicacies' such as peacock and swan, and fish -- carp, pike and so on,

which were cultivated in special fishponds."

Scientific

analysis

Matching up historic records from

the king's lifetime with brand new scientific data harvested from his remains

has offered experts a unique opportunity to "cross-check" what is

already known about his life and times.

As Richard Buckley, the

University of Leicester archaeologist in charge of the dig which uncovered the

king's remains, explained: "It is very rare indeed in archaeology to be

able to identify a named individual with precise dates and a documented life.

"This has enabled

stable-isotope analysis to show how his environment changed at different times

and, perhaps most significantly, identified marked changes in his diet when he

became king in 1483."

Isotope analysis backs up many of

the records of Richard's life -- that he was born in eastern England but spent

part of his childhood in western Britain. And knowing where he lived, from

ancient documents, allowed the experts to learn something new about isotope

analysis.

"By looking at the levels of

oxygen isotopes, we can tell where a person lived, because the oxygen comes

from the drinking water that they consumed," said Lamb.

"In this case, the isotopes

suggested that [towards the end of his life] Richard was living in the extreme

southwest of Britain, but we know from the records that this isn't the case, so

we had to look for another explanation."

Wine habit

Given the discoveries they had

already made about Richard's extravagant diet, they began to wonder if the

discrepancy in oxygen isotopes pointed to the fact he was drinking something

other than water.

Brewing water into ale is known

to alter isotope levels, but beer was not a high-status drink in the medieval

era.

"We needed something that

would tie in with the luxury food he would have been eating," said Lamb.

"Back then wine was very much the preserve of the upper classes -- it was

imported, expensive and only the very wealthy could afford it."

By carrying out tests with modern

equivalents, the scientists were able to conclude that Richard drank up to a

bottle of wine a day -- and to work out, for the first time, that wine

consumption affects oxygen isotope levels.

"It is fascinating,"

said Lamb. "We use these techniques all the time, but we are never able to

'cross-check' them, and it is only his which enabled us to figure it out."

No comments:

Post a Comment