Ini Surat Sutradara 'Jagal' Soal Capres Indonesia

http://pemilu.tempo.co/read/news/2014/06/27/269588510/Ini-Surat-Sutradara-Jagal-Soal-Capres-Indonesia

TEMPO.CO, Jakarta - Sutradara film Jagal (The Act of Killing) meraih nominasi film dokumenter terbaik Oscar, Joshua Oppenheimer menorehkan perhatiannya pada pemilihan presiden Indonesia dengan membuat surat terbuka kepada masyarakat Indonesia. Surat terbuka itu juga di-posting di laman Facebook milik Joshua, Jumat, 27 Juni 2014.

"Saya setuju dan bangga pernyataan saya 'Mengapa Saya Peduli dengan Pemilihan Presiden Indonesia' diterbitkan," kata Joshua kepada Tempo, Jumat sore, 27 Juni 2014.

Joshua dalam pernyataan terbukanya, antara lain mengatakan sisi gelap Indonesia dan secara umum sisi gelap kemanusiaan ini mewujudkan dalam satu calon presiden, Prabowo Subianto. "Sekalipun Prabowo sendiri tidak muncul dalam film Jagal," kata Joshua.

Berikut surat pernyataan terbuka Joshua yang diterbitkan dalam dua bahasa, Indonesia dan Inggris:

Film Jagal (The Act of Killing) memaparkan suasana hari ini yang dihantui korupsi, ketakutan, dan premanisme, kesemuanya dilandaskan pada impunitas atas pelanggaran berat hak asasi manusia berikut kejahatan terhadap kemanusiaan.

Film Jagal menggambarkan para oligarki yang menjarah sebuah bangsa yang bergelut dengan trauma, yang mengipasi kebencian rasis anti-Tionghoa, yang mengutus para preman untuk melaksanakan pekerjaan kotor mereka—termasuk membunuh dalam skala besar—untuk memperkaya diri mereka sendiri, dan untuk terus menggenggam kekuasaan.

Sisi gelap Indonesia dan secara umum sisi gelap kemanusiaan ini mewujud dalam satu calon presiden, Prabowo Subianto, sekalipun Prabowo sendiri tidak muncul dalam film Jagal.

Oleh karena itu saya berharap Jokowi akan terpilih sebagai presiden pada 9 Juli mendatang. Jokowi bukanlah seorang oligarki. Sebagai Gubernur DKI Jakarta, ia telah menunjukkan kepeduliannya pada problema rakyat kebanyakan, mungkin jauh lebih peduli daripada politisi yang manapun sejak genosida 1965, ketika Soeharto dan para kroninya mengubah pemerintahan menjadi kleptokrasi yang bertahan hingga hari ini. Kita bisa, setidaknya, berharap bahwa Jokowi akan membawa perjalanan politik nasional ke arah yang baru. Kita tak mungkin menggantungkan harapan seperti ini pada Prabowo.

Di atas segalanya, saya berharap Jokowi menang karena, tidak seperti pesaingnya, Jokowi tidak pernah melakukan pelanggaran hak asasi manusia. Jokowi tidak pernah menculik atau membunuh manusia lain, dan tidak pernah dituduh berbuat demikian.

Beberapa hari terakhir ini, banyak yang bertanya, mengapa saya peduli. Seringkali, pertanyaan tersebut diikuti dengan pertanyaan lanjutan: mengapa saya tidak memusatkan perhatian pada pelanggaran hak asasi manusia yang dilakukan oleh pemerintah negara saya sendiri, Amerika Serikat? Pada pertanyaan kedua, jawaban saya sederhana: Itulah yang sedang saya lakukan. Pemerintah negara saya juga adalah pelaku genosida 1965 di Indonesia, dan pelaku berbagai kejahatan di seluruh dunia.

Saya malu akan hal ini, demikian juga seharusnya warga Amerika Serikat yang lain. Dan kalau kita tidak munafik, kita harus menuntut penghentian impunitas di Tanah Air, bukan hanya di luar negeri. Lima puluh tahun terlalu lama untuk menyangkal bahwa sebuah genosida adalah ‘genosida.’ Sudah waktunya bagi Amerika Serikat, Inggris Raya, dan negara-negara lain yang mendukung genosida (juga pelanggaran HAM selanjutnya yang dilakukan rezim Orde Baru) mengakui peran mereka di dalam berbagai kejahatan ini, dan menjelaskan kepada publik rincian peran serta mereka. Seperti pemerintah Indonesia, pemerintah negara saya pun harus bertanggung jawab sepenuhnya atas perannya dalam pembantaian tersebut.

Tetapi saya peduli dengan hak-hak asasi manusia di Indonesia lebih karena alasan pribadi—lebih pribadi daripada karena saya telah menghabiskan 13 tahun bekerja dengan para penyintas dan pelaku pembunuhan massal 1965. Saya peduli karena saya percaya bahwa semua pelanggaran hak asasi manusia, semua kejahatan terhadap kemanusiaan, adalah kejahatan terhadap seluruh umat manusia di mana pun. Alasan yang sebaiknya juga melandasi kepedulian Anda.

Semua orang Indonesia, dan semua manusia di mana pun, harus mencegah seorang pelanggar HAM seperti Prabowo Subianto menjadi presiden.

Joshua Oppenheimer

Sutradara film The Act of Killing

MARIA RITA

"Saya setuju dan bangga pernyataan saya 'Mengapa Saya Peduli dengan Pemilihan Presiden Indonesia' diterbitkan," kata Joshua kepada Tempo, Jumat sore, 27 Juni 2014.

Joshua dalam pernyataan terbukanya, antara lain mengatakan sisi gelap Indonesia dan secara umum sisi gelap kemanusiaan ini mewujudkan dalam satu calon presiden, Prabowo Subianto. "Sekalipun Prabowo sendiri tidak muncul dalam film Jagal," kata Joshua.

Berikut surat pernyataan terbuka Joshua yang diterbitkan dalam dua bahasa, Indonesia dan Inggris:

Film Jagal (The Act of Killing) memaparkan suasana hari ini yang dihantui korupsi, ketakutan, dan premanisme, kesemuanya dilandaskan pada impunitas atas pelanggaran berat hak asasi manusia berikut kejahatan terhadap kemanusiaan.

Film Jagal menggambarkan para oligarki yang menjarah sebuah bangsa yang bergelut dengan trauma, yang mengipasi kebencian rasis anti-Tionghoa, yang mengutus para preman untuk melaksanakan pekerjaan kotor mereka—termasuk membunuh dalam skala besar—untuk memperkaya diri mereka sendiri, dan untuk terus menggenggam kekuasaan.

Sisi gelap Indonesia dan secara umum sisi gelap kemanusiaan ini mewujud dalam satu calon presiden, Prabowo Subianto, sekalipun Prabowo sendiri tidak muncul dalam film Jagal.

Oleh karena itu saya berharap Jokowi akan terpilih sebagai presiden pada 9 Juli mendatang. Jokowi bukanlah seorang oligarki. Sebagai Gubernur DKI Jakarta, ia telah menunjukkan kepeduliannya pada problema rakyat kebanyakan, mungkin jauh lebih peduli daripada politisi yang manapun sejak genosida 1965, ketika Soeharto dan para kroninya mengubah pemerintahan menjadi kleptokrasi yang bertahan hingga hari ini. Kita bisa, setidaknya, berharap bahwa Jokowi akan membawa perjalanan politik nasional ke arah yang baru. Kita tak mungkin menggantungkan harapan seperti ini pada Prabowo.

Di atas segalanya, saya berharap Jokowi menang karena, tidak seperti pesaingnya, Jokowi tidak pernah melakukan pelanggaran hak asasi manusia. Jokowi tidak pernah menculik atau membunuh manusia lain, dan tidak pernah dituduh berbuat demikian.

Beberapa hari terakhir ini, banyak yang bertanya, mengapa saya peduli. Seringkali, pertanyaan tersebut diikuti dengan pertanyaan lanjutan: mengapa saya tidak memusatkan perhatian pada pelanggaran hak asasi manusia yang dilakukan oleh pemerintah negara saya sendiri, Amerika Serikat? Pada pertanyaan kedua, jawaban saya sederhana: Itulah yang sedang saya lakukan. Pemerintah negara saya juga adalah pelaku genosida 1965 di Indonesia, dan pelaku berbagai kejahatan di seluruh dunia.

Saya malu akan hal ini, demikian juga seharusnya warga Amerika Serikat yang lain. Dan kalau kita tidak munafik, kita harus menuntut penghentian impunitas di Tanah Air, bukan hanya di luar negeri. Lima puluh tahun terlalu lama untuk menyangkal bahwa sebuah genosida adalah ‘genosida.’ Sudah waktunya bagi Amerika Serikat, Inggris Raya, dan negara-negara lain yang mendukung genosida (juga pelanggaran HAM selanjutnya yang dilakukan rezim Orde Baru) mengakui peran mereka di dalam berbagai kejahatan ini, dan menjelaskan kepada publik rincian peran serta mereka. Seperti pemerintah Indonesia, pemerintah negara saya pun harus bertanggung jawab sepenuhnya atas perannya dalam pembantaian tersebut.

Tetapi saya peduli dengan hak-hak asasi manusia di Indonesia lebih karena alasan pribadi—lebih pribadi daripada karena saya telah menghabiskan 13 tahun bekerja dengan para penyintas dan pelaku pembunuhan massal 1965. Saya peduli karena saya percaya bahwa semua pelanggaran hak asasi manusia, semua kejahatan terhadap kemanusiaan, adalah kejahatan terhadap seluruh umat manusia di mana pun. Alasan yang sebaiknya juga melandasi kepedulian Anda.

Semua orang Indonesia, dan semua manusia di mana pun, harus mencegah seorang pelanggar HAM seperti Prabowo Subianto menjadi presiden.

Joshua Oppenheimer

Sutradara film The Act of Killing

MARIA RITA

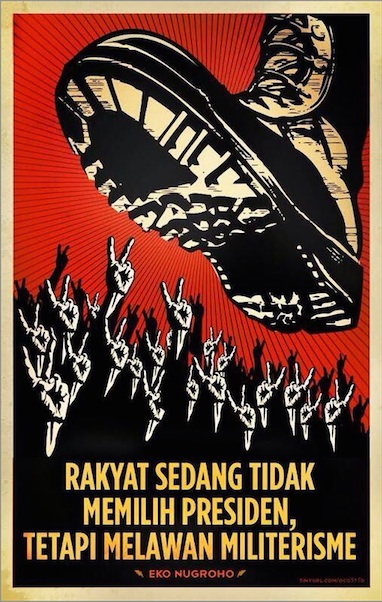

KAMPANYE HITAM: HANTU LEE ATWATER ... DI INDONESIA?

http://indoprogress.com/2014/06/kampanye-hitam-hantu-lee-atwater-di-indonesia/

TIDAKada orang yang dianggap paling bedebah dalam sejarah politik modern Amerika selain Harvey LeRoy ‘Lee’ Atwater. Dia adalah ahli strategi, tukang plintir (spin doctor) nomor wahid, jagoan dalam hal intrik, jenius dalam memanipulasi. Lee Atwater adalah seorang operator politik. Dia bukan politisi. Tapi dia mampu mendudukkan politisi pada satu jabatan tertentu. Atwater adalah ‘Darth Vader’-nya politik Amerika. Orang yang sangat tega dan ganas, yang mampu melakukan apa saja agar klien-nya terpilih.

Lee Atwater memulai karirnya sebagai konsultan politik di selatan Amerika. Ini adalah daerah yang dalam sejarah perang saudara Amerika dikenal sebagai wilayah ‘Confederate.’ Penduduk wilayah ini anti-penghapusan perbudakan. Ini karena sebagian besar wilayahnya adalah wilayah pertanian. Salah satu warisan dari perbudakan ini adalah politik ras. Namun, sekalipun daerah-daerah ini sangat tersegregasi menurut warna kulit, politik ras tidak muncul ke permukaan hingga tahun 1960an. Sebelum itu, daerah-daerah ini adalah wilayah partai Demokrat. Karena orang kulit hitam tidak bisa memilih, maka pemilih kulit putih lebih mengutamakan kelas. Demokrat, yang progresif dan berorientasi pada kelas pekerja, selalu menjadi mayoritas di situ. Namun itu tidak berlaku di akhir tahun 1960an.

Adalah Richard Nixon yang mengubah peta politik di wilayah tersebut. Setelah UU Hak-hak Sipil (Civil Rights Act)disahkan Presiden Lyndon B. Johnson (Demokrat) tahun 1964, diskriminasi terhadap orang kulit hitam dihapuskan. Yang paling penting dari UU ini, selain penghapusan diskriminasi atas dasar ras, warna kulit, agama, jenis kelamin, atau kebangsaan, adalah pemberian hak memilih untuk orang kulit hitam. UU ini mengubah semua dimensi politik di wilayah Selatan. Nixon memperhatikan ini dengan cermat. Dia memanipulasi politik di wilayah itu untuk menarik suara kaum kulit putih. Dan itu berhasil dengan baik.

Strategi untuk menggalang suara berdasarkan ras ini dikenal dengan nama ‘the Southern strategy.’ Karena diskriminasi atas nama apapun dilarang secara hukum, maka para operator politik bekerja dengan bahasa ‘kode.’ Mereka tidak mengungkapkan secara terbuka kebenciannya kepada orang kulit hitam, tetapi lewat kode-kode, seperti, misalnya, kerawanan sosial (artinya: orang kulit hitam itu kriminal); kupon makanan (orang kulit hitam itu pemalas dan jadi beban karena pajak yang Anda bayar dipakai untuk mensubsidi makanan mereka); rumah bersubsidi; jaminan sosial, dan lain sebagainya. Politik ini juga dikenal dengan nama politik ‘siulan anjing’ (dog whistle politics). Karena ada siulan anjing yang frekuensi suaranya hanya bisa didengar oleh anjing tapi tidak oleh manusia.

Inilah keahlian Lee Atwater. Dia memulai karirnya dengan menjadi operator politik senator Strom Thurmond dari negara bagian South Carolina. Senator ini terkenal sebagai pendukung politik segregasi dan penentang pemberian hak-hak sipil untuk kaum kulit hitam. Namun, beberapa bulan setelah dia meninggal, terungkap bahwa dia memiliki seorang putri dari seorang perempuan kulit hitam yang bekerja di rumahnya (sangat khas Amerika!). Saat bekerja untuk Senator Thurmond inilah Lee Atwater mengembangkan bakatnya sebagai bedebah politik. Dia membikin konferensi pers dengan menanam beberapa orang reporter palsu di antara reporter betulan. Reporter palsu ini mengajukan pertanyaan-pertanyaan yang memojokkan lawan politiknya. Dia juga mengirim surat-surat langsung ke pemilih (direct mail) yang memberikan informasi palsu tentang lawan politiknya. Lee juga ahli dalam memanipulasi media. Dia akan memberikan informasi off the record tentang lawan politiknya kepada media – dan karena dia memiliki kualitas kepribadian yang demikian meyakinkan maka si wartawan merasa tidak perlu melakukan cross-checking. Dia juga membikin survey-survey palsu yang menunjukkan keunggulan calonnya. Survey-survey ini diharapkan akan memunculkan ‘band-wagon effect’ yaitu efek seperti gerbong yang menarik gerbong lainnya.

Lee Atwater berjasa membantu kemenangan Ronald Reagan di wilayah Selatan, yang kemudian membawa Reagan ke tampuk kepresidenan pada 1980. Lee kemudian ikut ke Washington dan menjadi wakil direktur urusan politik Gedung Putih. Dia juga wakil manajer kampanye pemilihan kembali Reagan tahun 1984. Manajer kampanye Reagan saat itu, Ed Rollins, menyebut Atwater menjalankan ‘taktik-taktik kotor’ khususnya terhadap calon wakil presiden Geraldine Ferraro (perempuan pertama yang menjadi calon wakil presiden Amerika!). Atwater mengampanyekan bahwa orangtua Geraldin Ferraro pernah ditahan karena berjualan togel (toto gelap).

Prestasi utama Atwater adalah pada 1988 ketika dia menjalankan kampanye George H.W. Bush Sr. Ketika itu, kampanye Bush hancur berantakan. Opini publik pada musim panas menunjukkan posisi Bush pada angka -17 persen. Namun saat pemilihan bulan November, Lee Atwater menjungkirbalikkan keadaan itu. Lawan Bush, Gubernur negara bagian Massachusetts, Michael Dukakis, diserang dengan taktik paling kotor yang pernah dipakai dalam pemilu AS. Lee Atwater memproduksi sebuah video kampanye yang menggambarkan seorang terpidana yang bernama Willie Horton. Disana digambarkan Bush sebagai orang yang pro hukuman mati; sementara Dukakis adalah anti-hukuman mati. Tidak itu saja, Dukakis disebutkan mendukung program yang membolehkan tahanan keluar penjara saat akhir pekan. Di sinilah Willie Horton mengambil peranan. Pria kulit hitam ini dihukum seumur hidup, tetapi boleh menikmati ‘liburan’ akhir pekan keluar penjara. Semasa ‘liburan’ itulah Horton menyerang dua orang yang berpasangan, membacok, dan memperkosa yang perempuan.

Iklan ini jelas adalah sebuah ‘kode.’ Dalam konteks rasial masyarakat Amerika, ini adalah kode lunaknya Dukakis terhadap orang kulit hitam. Tidak itu saja. Penekanan rasial dalam video kampanye ini mengirimkan sinyal kepada ras kulit putih, yang menjadi mayoritas pemilih: keamanan Anda menjadi taruhan kalau Anda memilih Dukakis! Para kriminal itu (baca: kulit hitam) akan bebas berkeliaran untuk merampok, membunuh, dan memperkosa.

Iklan Willie Horton itu menjadi sangat fenomenal. Bukan karena keberhasilannya dalam menjungkirbalikan posisi politik Bush sehingga membuat dia terpilih sebagai presiden, tetapi karena unsur rasialnya. Iklan ini memainkan emosi dan ketakutan tidak beralasan orang kulit putih terhadap kulit hitam. Ia menguatkan semua prasangka yang memang sudah ada dan menyuburkannya. Ia mampu menghimpunorang kulit putih berbondong-bondong mencoblos (pemilihan bukan suatu kewajiban di Amerika).

Kampanye model ini tidak terjadi sekali dua kali saja. Hampir setiap periode pemilihan pasti diwarnai oleh kampanye hitam ini. Ada yang ditempuh dengan bisik-bisik, ada juga lewat bombardir iklan TV yang menyesatkan. Ambillah contoh kampanye Senator John McCain pada tahun 2000. Saat kampanye penyisihan (primary campaign) untuk menjadi calon Partai Republik, McCain harus menghadapi tuduhan bahwa dia memiliki anak kulit hitam hasil hubungan gelapnya. McCain memang memiliki putri angkat yang berasal dari Bangladesh. Pahlawan perang Vietnam ini memang sedang memperoleh momentum karena kemenangannya di New Hampsire. Lawannya adalah George W. Bush Jr, yang kemudian menjadi presiden. Ketika pemilihan di South Carolina, McCain harus menghadapi tuduhan ini, yang disebarkan lewat selebaran dari rumah ke rumah. Inilah yang membuatnya terjungkal dan George Bush menjadi calon presiden dari Partai Republik.

Hal yang sama juga dialami John Kerry pada tahun 2004. Kerry, seorang veteran perang Vietnam, menerima medalithe purple heart karena terluka di Vietnam. Pada kampanye pemilihan presiden melawan George Bush, Kerry diserang lewat iklan kampanye oleh kelompok yang menamakan dirinya Swift Boat Veterans for Truth. Kelompok ini mempertanyakan medali yang diterima Kerry, terutama karena Kerry pernah bersaksi di depan Kongres tentang kekejaman tentara Amerika di Vietnam. Para veteran, yang terluka atau yang pernah ditawan itu bertanya, ‘Jika Kerry tidak loyal terhadap kawan seperjuangannya, bagaimana dia bisa loyal terhadap negara?’

Ada satu hal yang juga penting digarisbawahi baik pada kampanye hitam ataupun kampanye negatif. Yang diserang bukan bagian yang lemah dari lawan politiknya. Namun, justru yang paling kuat. Dukakis diserang karena kebijakannya yang ingin memperbaiki sistem ‘pemasyarakatan.’ Dia justru ingin sistem yang lebih manusiawi. McCain diserang karena integritasnya, baik sebagai mantan tawanan perang Vietnam, maupun karena sikapnya yang terus terang. Tuduhan memiliki anak dari hasil hubungan gelap adalah serangan yang paling fatal atas integritas dan kejujurannya. Kerry diserang, persis karena statusnya sebagai penerima medali purple heart. Dia menjadi pengritik perang Vietnam. Posisi ini sebenarnya sangat populer di kalangan masyarakat Amerika. Namun, para ahli strategi di pihak Bush dengan buas mengeskploitasinya menjadi titik lemahKerry, yakni dengan menghubungkannya dengan loyalitas terhadap kawan seperjuangan. Bush berhasil mengeksploitasi sentimen nasionalisme.

‘Jokowi! Jokowi! Orangnya belum sunat!’ Demikianlah celoteh anak-anak kecil yang didengar oleh sastrawan AS Laksana di dekat rumahnya. Tentu saja ini diucapkan sambil bermain. Namun ada sesuatu yang serius di sini. Permainan anak-anak itu menjadi sebuah pertanda bahwa smear campaign (kampanye fitnah) yang dilancarkan oleh kubu lawan Jokowi itu bekerja dengan baik. Dia sudah sampai ke tingkat anak-anak. Jika para orangtua hanya mendengarnya lewat bisik-bisik, anak-anak meneruskannya menjadi pengumuman.

Yang jelas, kampanye hitam hadir dalam pemilihan presiden Indonesia 2014. Bahkan, dia hadir dalam skala yang tidak pernah terlihat sebelumnya. Kampanye hitam lebih banyak ditujukan kepada kandidat Joko Widodo (Jokowi) ketimbang Prabowo Subianto. Mengapa? Ini karena problem berbeda yang dihadapi oleh kedua calon. Masalah utama yang harus dihadapi oleh Prabowo Subianto adalah data, terutama data sejarah yang berupa rekam jejaknya pada masa lalu. Sementara, tantangan utama Joko Widodo adalah kampanye hitam baik dalam bentuk disinformasi, tuduhan rasial dan agama, maupun rekam jejak dalam kehidupan publiknya sebagai politisi.

Prabowo Subianto memiliki beban ‘data masa lalu’ yang cukup berat, yang mungkin tidak akan berhenti dipertanyakan, bahkan kalau dia terpilih menjadi presiden. Namun, di balik semua itu, Prabowo jelas figur yang lebih dikenal oleh publik Indonesia ketimbang Jokowi. Jika Prabowo bagaikan sebuah buku novel, maka Jokowi bagaikan buku kosong yang perlu ditulis. Semua orang tahu akan sepak terjang Prabowo, mulai dari kakeknya, ayahnya, dan mertuanya (Suharto). Juga rekam jejaknya sebagai perwira militer, tingkah lakunya dalam banyak kasus pelanggaran HAM, dan kehidupannya sesudah dipecat dari dinas militer. Terlebih lagi, setelah ‘dipecat dengan hormat’ dari dinas militer, Prabowo menghabiskan hampir seluruh karirnya untuk berkampanye menjadi Presiden Republik Indonesia.

Sebaliknya, Jokowi adalah figur yang baru melejit ke publik selama dua tahun terakhir ini. Sebelum itu dia hanya dikenal di lingkup Surakarta, Jawa Tengah, dimana dia menjadi walikota. Dia mulai mendapat perhatian luas dari publik saat dia mencalonkan diri untuk gubernur DKI Jakarta. Sejak saat itu, karir politiknya menanjak tajam. Namun, tidak banyak orang kenal siapa dia. Pengetahuan publik hanya terbatas pada apa yang dia kerjakan sebagai walikota Surakarta dan sebentar menjadi gubernur DKI Jakarta. Itulah sebabnya, Jokowi itu bagaikan buku kosong yang butuh untuk diisi tulisan. Di sinilah lawan dan sekutu politiknya berusaha untuk mengisi halaman-halaman buku itu. Lawan dan kawan politik Jokowi berusaha memberikan definisi tentang siapa Jokowi sebenarnya.

Persis di titik itu kampanye hitam bekerja. Lawan-lawan Jokowi segera masuk mengisi ruang kosong ini. Persis seperti Lee Atwater memberikan kode rasial kepada pemilih Amerika tahun 1988, bahwa memilih Dukakis berarti memihak pada orang kulit hitam. Implikasinya adalah kriminalitas akan menanjak, dominasi orang kulit putih akan melemah, dan secara otomatis akan mengubah tatanan rasial yang sudah ada. Kampanye Lee Atwater memainkan ketakutan orang-orang kulit putih.

Hal yang sama berlaku untuk Jokowi. Lawan-lawan politiknya berusaha mendefinisikan Jokowi sebagai Kristen dan keturunan Cina. Dia dituduh menyembunyikan identitas kekeristenan dan kecinaannya. Dalam kampanye fitnah tersebut, nama asli Jokowi adalah Herbertus Handoko Joko Widodo bin Oey Hong Liong (Noto Mihardjo). Foto Jokowi saat menikah beredar yang mengungkapkan bahwa dia adalah keturunan Cina yang menyembunyikan identitas sukunya (a closet Chinese). Sementara itu juga beredar iklan dukacita, lengkap dengan aksara Cina. Iklan itu juga menginsinuasi bahwa Jokowi adalah Kristen keturunan Cina.

Kampanye hitam ini adalah fitnah (smear campaign) secara membabi buta. Jika kampanye hitam di Amerika pada umumnya ditujukan kepada orang kulit putih dan memainkan ketakutan rasial mereka, maka di Indonesia kampanye ini secara khusus ditujukan kepada kalangan Muslim. Kampanye ini memainkan perasaan kalangan Muslim Indonesia, terutama ketakutan akan dikuasai oleh Kristen. Setelah Suharto tumbang, sektarianisme berdasarkan agama memang menguat di Indonesia. Ini menyumbang pada ketakutan bahwa umat Islam akan diperintah oleh orang beragama Kristen. Sementara, sentimen anti-Cina pun masih kuat di bawah permukaan. Sekalipun setelah Suharto jatuh kerusuhan rasial anti-Cina sangat berkurang drastis namun prasangka rasial terhadap orang Cina masih sangat kuat. Prasangka rasial ini memang tidak muncul ke permukaan. Tapi dia menjadi semacam ‘hidden transcript’ di kalangan masyarakat Indonesia. Dia dibicarakan di ruang-ruang keluarga, di dalam suasana yang akrab, dan jarang muncul ke publik. Namun ia ada.

Seiring dengan berjalannya kampanye pemilihan presiden, tekanan kampanye hitam ini makin menghebat. Serangan terhadap Jokowi tidak saja berlangsung dari mulut ke mulut dan lewat media sosial. Ia kemudian ditingkatkan ke dalam bentuk tabloid yakni Obor Rakyat. Tabloid ini secara samar-sama memiliki kaitan dengan kampanye Prabowo-Hatta. Tabloid ini pun diedarkan dengan target yang jelas, yakni kalangan Islam khususnya basis-basis Islam tradisional, Nahdlatul Ulama (NU). Isinya sebagian besar memperkuat apa yang sudah didengar sebelumnya. Obor Rakyat agaknya akan menjadi cara baru kampanye di Indonesia. Dia menyamarkan diri sebagai karya jurnalistik, walaupun sesungguhnya dia menunggangi dunia jurnalisme untuk melancarkan kampanye hitam.

Setiyardi, asisten staf khusus Presiden, pemred Obor Rakyat, media corong kampanye hitam

Setelah beberapa minggu mengamati kampanye pemilihan presiden di Indonesia, saya mendapati betapa mirip pola-pola kampanye ini dilakukan menurut ‘political campaign playbook’ yang dijalankan dalam politik Amerika. Ini secara khusus tampak di kubu Prabowo Subianto. Serangan-serangan, baik yang dibawah tanah dalam bentuk kampanye hitam maupun di atas permukaan dalam serangan politik formal, terlihat sangat biasa untuk mereka yang biasa mengamati politik Amerika.

Di atas permukaan, serangan paling awal terhadap Jokowi adalah sebagai presiden ‘boneka.’ Uniknya, dia tidak dituduh sebagai boneka asing (baru kemudian tuduhan itu muncul) tetapi sebagai boneka Megawati Sukarnoputri, ketua PDIP, partai yang mencalonkan Jokowi. Kubu Prabowo-Hatta tahu persis bahwa kekuatan Jokowi bukan karena dukungan PDIP terhadap dirinya. Kekuatan utamanya adalah populisme yang melintasi garis partai. Jokowi maju bertarung untuk kursi kepresidenan karena ‘diwajibkan’ (conscripted) oleh kalangan independen.

Para ahli strategi di kubu Prabowo berusaha mementahkan ini dengan ‘mengembalikan’ Jokowi kepada Megawati yang popularitasnya memang sangat rendah di kalangan pemilih Indonesia. Menyerang kekuatan lawan, dan bukan kelemahannya, adalah sesuatu yang sangat umum terjadi di dalam poltik Amerika.

Namun serangan yang paling berhasil adalah dalam bentuk kampanye hitam (atau lebih tepatnya smear campaign – kampanye fitnah). Kampanye ini dilakukan oleh kelompok-kelompok di luar tim kampanye resmi. Serangannya pun sangat frontal dan mematikan. Dia menusuk langsung ke psyche masyarakat Indonesia, memainkan ketakutan-ketakutan sektarian dan rasial. Kampanye model ini dipakai karena hasilnya luar biasa bagus. Kampanye hitam, selain memberikan definisi tentang siapa Jokowi itu juga berfungsi untuk mobilisasi.1 Orang-orang yang ketakutan akan berbondong-bondong memenuhi bilik-bilik suara.

Sedemikian miripnya serangan-serangan dan organisasi kampanye Prabowo-Hatta dengan pola-pola kampanye di Amerika, tentu membuat kita bertanya-tanya: Adakah campur tangan operator politik yang berpengalaman dalam politik Amerika dalam mengelola kampanye Prabowo? Selama ini, pers Indonesia meributkan bahwa kubu Prabowo Subianto mendapatkan bantuan dari konsultan politik Amerika dari Partai Republik yang bernama, Rob Allyn. Kubu Prabowo membantah bahwa Allyn memberikan konsultasi. Namun mereka tidak membantah kalau Allyn bekerja untuk perusahan yang dikontrak oleh tim kampanye kubu Prabowo.2

Rob Allyn mungkin bukan figur yang penting dalam politik Amerika. Satu-satunya prestasi paling penting Allyn adalah membuat Gubernur George W. Bush terpilih kembali di Texas tahun 1994. Allyn lebih banyak menangani politisi lokal di AS. Namun, Allyn dan perusahan konsultannya memiliki nama besar di luar AS. Dia berhasil menaikkan Vincente Fox menjadi presiden Meksiko tahun 2000.3 Sejak itu, Allyn mengembangkan usahanya di luar AS. Dia mulai bergerak di Indonesia diperkirakan sekitar tahun 2004, dengan menjadi konsultan politik untuk Partai Golkar.4 Saat ini, Allyn mengaku kepada Dallas Observer bahwa dia hidup selama sembilan bulan dalam setahun di Indonesia.

Mungkin ada tangan Rob Allyn dalam membangun strategi kampanye di kubu Prabowo. Mungkin juga tidak. Akan tetapi warna Amerika sangat kuat tercermin dalam kampanye Presiden Indonesia 2014.

Terakhir, apa konsekuensi kampanye hitam terhadap politisi yang berhasil terpilih ke tampuk kekuasaan? Saya melihat dua konsekuensi penting. Pertama, terhadap lawan politiknya. Seorang politisi yang terpilih menduduki satu jabatan, tetap memerlukan lawannya ketika dia memerintah. Jika kampanye adalah persoalan memecah-belah dan berusaha mencari suara yang terbanyak, memerintah (governing) adalah persoalan mempersatukan. Politisi yang dikalahkan dengan kampanye hitam akan sulit menghilangkan ‘rasa getir’ kekalahannya itu. Demikian pula pendukung-pendukungnya. Jika ini terjadi, persoalan memerintah menjadi makin sulit; oposisi semakin sulit untuk diajak bekerja sama; dan pada akhirnya akan menentukan berhasil tidaknya pemerintah yang berkuasa. Kedua,adalah ke dalam koalisi pihak yang memerintah itu sendiri. Kebanyakan kampanye hitam dilakukan secara rahasia, oleh kelompok rahasia, dan disokong oleh dana-dana gelap. Setelah berkuasa, maka penguasa harus berurusan dengan kelompok-kelompok rahasia yang membantunya menaikkan dirinya ke kekuasaan. Sangat lumrah kelompok-kelompok ini tidak puas, dan akhirnya membuka semua aib pihak yang berkuasa dan menjadikannya skandal. Kerahasian (secretiveness) selalu memiliki harga mahal yang harus dibayar.

Pemerintahan yang dihasilkan lewat kampanye hitam berlebihan akan terus menerus berada dalam mode kampanye dan tidak sempat memerintah. Untuk itu, presiden terpilih harus tetap dikelilingi oleh konsultan-konsultan politik. Jika dia menang dalam pemilihan 9 Juli nanti, Presiden Prabowo Subianto mungkin juga harus mencari konsultan politik yang baru, yakni konsultan yang menangani cara memerintah. Kali ini, mungkin konsultan tersebut harus datang dari Russia, mengingat betapa kuatnya Presiden Putin berkuasa di sana.***

Penulis adalah peneliti masalah-masalah politik militer dan jurnalis lepas (freelance). Tulisannya pernah muncul di Prisma, Jurnal Indonesia, dan Inside Indonesia.

1Lihat, misalnya, Paul S. Martin, ‘Inside the Black Box of Negative Campaign Effects: Three Reasons Why Negative Campaigns Mobilize,’ Political Psychology, Vol. 25, No. 4, Symposium on Campaigns and Elections (Aug., 2004), pp. 545-562

2Lihat keterangan Haryanto Taslam, http://nasional.inilah.com/read/detail/108985/prabowo-sewa-konsultan-bush#.U6u38ZRdXHQ

4http://www.nytimes.com/2005/12/28/business/media/28adco.html Harian The New York Times, 28 Desember 2006 menyebutkan bahwa Allyn bekerja untuk Partai Golkar. Ada kemungkinan bahwa Allyn membantu Prabowo untuk memenangkan konvensi Partai Golkar saat itu dan tidak secara langsung membantu Partai Golkar.

Indonesien: Wahlkampf in Himmlers SS-Uniform

http://www.spiegel.de/politik/ausland/indonesien-ss-uniform-von-heinrich-himmler-in-wahlkampf-video-a-977207.html

Sänger Ahmad Dhani in Himmler-Uniform: "Indonesien erwache!"

"We Will Rock You" in Nazi-Ästhetik: Ex-General Prabowo Subianto setzt im Kampf um das indonesische Präsidentenamt auf martialisches Auftreten - und auf einen Sänger in Heinrich-Himmler-Uniform. Bei den Wählern kommt das an.

Jakarta - In zwei Wochen wählt das größte islamische Land der Welt einen neuen Staatschef. Mehr als 185 Millionen Indonesier haben am 9. Juli die Wahl zwischen zwei Präsidentschaftskandidaten - dem Gouverneur der Hauptstadt Jakarta, Joko Widodo, und Ex-General Prabowo Subianto.

Der charismatische Widodo, Spitzname Jokowi, geht als Favorit in die letzten Wochen des Wahlkampfs. Doch sein Gegenkandidat zieht alle Register. Für den Schlussspurt veröffentlichte Prabowos Wahlkampfteam einen Song, der besonders die jungen Indonesier begeistern soll.

Zur Melodie des Queen-Klassikers "We Will Rock You" skandieren vier prominente indonesische Popstars die Namen von Prabowo und seinem Vize-Kandidaten Hatta Rajasa. Weiter heißt es im Text: "Indonesien erwache, Wer sonst vermag Indonesien zu erwecken aus seiner Misere? Wer sonst, wenn nicht wir?"

Prabowo spielt mit Nazi-Ästhetik

Brisanter als der Songtext ist jedoch das Outfit des Sängers Ahmad Dhani. Er trägt eine schwarze Uniformjacke, die der Uniform von SS-Führer Heinrich Himmler zum Verwechseln ähnelt. Dhani trägt die gleichen Kragenspiegel und den sogenannten Blutorden auf der Brust.

DPA

SS-Führer Himmler: Spiel mit der Nazi-Ästhetik

Diese bewusst inszenierte Assoziation mit Symbolen des Nazi-Regimes findet in Indonesien regen Anklang. Das "Dritte Reich" gilt vielen als Vorbild in puncto militärischer Stärke und staatlicher Effizienz. Adolf Hitlers "Mein Kampf" wird in vielen Buchläden verkauft. In der Stadt Bandung gibt es sogar ein Café, in dem Kellner in SS-Uniformen Speisen und Getränke servieren.

Auch Präsidentschaftskandidat Prabowo setzt in seinem Wahlkampf auf Militärästhetik. Auf seiner offiziellen Facebook-Seite zeigt sich der Politiker in den Uniformen der Miliz seiner Gerindra-Partei, der "Bewegung für ein Großindonesien".

Furcht vor Wahlsieg des Ex-Generals

Prabowo ist der Ex-Schwiegersohn des langjährigen Diktators Suharto. Als General befehligte er in den Achtziger- und Neunzigerjahren Massaker in der Unruheprovinz Osttimor. Zuvor war er unter anderem von der GSG 9 in der Bundesrepublik ausgebildet worden.

Nach dem Sturz seines Schwiegervaters 1998 ging Prabowo für einige Zeit ins Exil nach Jordanien. Nach seiner Rückkehr in die Heimat gründete er 2008 die Gerindra-Partei.

Im aktuellen Wahlkampf galt er lange als aussichtslos im Duell mit seinem Widersacher Jokowi. In den vergangenen Wochen hat sich der Abstand zwischen den beiden Spitzenkandidaten in den Umfragen rapide verringert. Inzwischen gehen die Medien in Indonesien von einem Kopf-an-Kopf-Rennen aus.

Demokratieaktivisten und Journalisten fürchten bei einem Wahlsieg Prabowos einen Rückfall in die dunklen Zeiten der Diktatur.

syd

YouTube removes Nazi-themed Indonesian

video based on Queen hit

http://www.theguardian.com/world/2014/jun/27/youtube-removes-indonesian-nazi-themed-video-emi-queen-we-will-rock-you

A man watches rock star Ahmad Dhani in the video Indonesia Bangkit. Photograph: Bagus Indahono/EPA

A Nazi-themed video performed by Indonesian musicians based on Queen's We Will Rock has been removed by YouTube after a copyright claim by EMIMusic Publishing.

Indonesia Bangkit, or Awakening Indonesia, sparked international outrage when it showed Indonesian rocker Ahmad Dhani in black military uniform and dark sunglasses holding a huge golden garuda bird, Indonesia's national emblem, and other singers performing the song with lyrics supporting Prabowo Subianto, a candidate in the presidential election on 9 July.

Critics said Dhani was wearing a military jacket identical to that often worn by SS chief Heinrich Himmler. Indonesian-born singer and songwriter Anggun Cipta Sasmi tweeted that the video had left her "shocked, disappointed and ashamed".

She added: "I pray that Indonesia does not descend into fascism."

Daniel Ziv, a Bali-based filmmaker, described the video as bringing "Nazi skinhead imagery to Indonesian politics".

Brian May, Queen's lead guitarist, has objected to the purloining of the song, tweeting: "Of course this is completely unauthorised by us."

The video was uploaded to YouTube on 19 June as a campaign song for Prabowo, a former general who has been accused of abducting pro-democracy activists in 1998. Although it can no longer be seen on YouTube, it can still be viewed at a number of media sites, including US news magazine Time.

Dhani, who is partly Jewish, has remained defiant despite the uproar.

"What's the connection between German soldiers and Indonesia?" was his comment to Indonesian media. "What's the connection between German soldiers and Indonesian musicians? We, the Indonesian people, didn't kill millions of Jewish people, right?"

Dhani's music video for Prabowo was released shortly after pop musicians including Oppie Andaresta and rock band Slank, who support Joko "Jokowi" Widodo – the governor of Jakarta and frontrunner – made their own song and music video, called Two-Finger Salute. With the vote imminent, supporters of both presidential candidates are using social media aimed at young, urban voters.

The latest poll supports most other recent polls showing Jokowi ahead, but with the size of his lead narrowing. Most also show a sizeable percentage of undecided voters. The state-funded Indonesian Institute of Sciences survey of 790 voters from 5-24 June found 43% support for Jokowi and 34% for Prabowo.

A controversial figure, Prabowo was discharged from military service in 1998 over the abduction of pro-democracy activists. He has appeared at campaign rallies on horseback before an honour guard, in keeping with the strongman image he likes to project.

Allan Nairn, an American journalist who has covered Indonesia extensively, posted on his blog a 2001 interview in which Prabowo said that Indonesia needed "a benign authoritarian regime". The former general, who made clear his admiration toward Pakistan's then ruling strongman Pervez Musharraf, told Nairn: "Do I have the guts, am I ready to be called a fascist dictator? Musharraf had the guts."

Nairn on Thursday challenged Prabowo's campaign to carry out its threat to have him arrested because of what he had written about the general.

"General Prabowo, the brother of a billionaire, was the son-in-law of the dictator Suharto, and as a US trainee and protégé was implicated in torture, kidnap and mass murder," wrote Nairn.