Indonesia presidential election explained

http://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-28167596

The governor of Jakarta and an ex-army general go head-to-head in a closely contested election on Wednesday to choose the next president of Indonesia, the country with the world's largest Muslim population.

It is the third direct presidential election since the collapse of the autocratic regime of Suharto in 1998.

Who is standing?

Joko Widodo is seen as the anti-establishment candidate

Joko Widodo, a businessman-turned-governor of Jakarta, and his running mate Jusuf Kalla, a former vice-president, are competing against former army general Prabowo Subianto and former economy minister Hatta Radjasa.

Mr Widodo, representing the Indonesian Democratic Party of Struggle (PDI-P), has been portrayed as a humble man of the people. He is known as an effective administrator and has sought to portray himself as the candidate from outside the establishment.

Mr Subianto, who leads the Greater Indonesia Movement Party (Gerindra), has modelled himself as a strong leader. But he has also had to contend with allegations of human rights abuses during his time at the helm of Suharto's special forces in the late 1990s.

What is at stake?

Both campaigns have used nationalistic rhetoric on the economy, corruption and other domestic issues such as infrastructure, education and social security.

Mr Widodo has pledged to boost Indonesia's productivity by supporting small and micro businesses and improving the financial system.

Mr Subianto has campaigned for stronger domestic control of the economy and limiting the role of foreign investors in the oil and gas sectors. He has also promised to reduce the "leakage" of Indonesia's assets which, according to his team, costs $84.5bn (£49.3bn) annually.

But a lack of detailed policies from either on how to create jobs or help boost economic growth has worried a lot of voters.

Prabowo Subianto has been a key figure in Indonesia for decades

What is their approach to foreign policy?

Mr Subianto has stressed the importance of military might, saying international respect is based on prowess.

Mr Widodo wants to strengthen ties between Indonesia and other countries through streamlined diplomacy, saying military engagement is a last resort to resolve disputes.

Neither has been clear on Indonesia's foreign policy goals in South East Asia, and neither has put forward a definite stance on the growing tension in the South China Sea.

The race has tightened in recent months

Who is going to win?

Polls suggest it will be a very tight race. Mr Widodo has led throughout the campaign, at one point having a 30-point lead. But the latest surveys suggest his lead has shrunk to less than five points.

Commentators say undecided voters will have a significant impact on results. About one-fifth of Indonesians fell in this category in the late June surveys.

How does it work?

Some 186 million people are eligible to vote. They will elect the president in a single round. Which ever candidate receives the most votes will win, and will serve for five years.

The official result will be announced on 21-22 July. The new president will be inaugurated on 20 October and will have to appoint a cabinet within two weeks.

Five reasons why Indonesia's presidential election matters

http://www.theguardian.com/world/2014/jul/07/five-reasons-why-indonesia-presidential-election-matters

Once a dictatorship, now the world's third largest democracy, the 90% Muslim country is poised to take a step forward

The 187 million Indonesian voters are taking part in the first election to see power transferred from one democratically elected leader to another. Photograph: Beawiharta/Reuters

1. Mega Democracy

Indonesia is the world's third largest democracy, with 187 million voters, including 67 million first-time voters. More importantly, this election is the first time that power will be handed over from one directly elected leader to another. The incumbent, Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono, is the country's first directly elected president, who took office after the fall of the former authoritarian ruler Suharto in 1998. After serving a maximum two five-year terms in office, Yudhoyono is ineligible to seek a third term.

One of the Mint countries, Indonesia's economy is enjoying healthy growth. Photograph: Adi Weda/EPA

2. Healthy economy

Indonesia is an increasingly important economy. Crippled by the Asian financial crisis of 1998, today it is south-east Asia's largest economy, a member of G20 and one of the best performing economies globally. Counted among the Mints (Morocco, Indonesia, Nigeria and Turkey), a new group of emerging market economies, Indonesia's economy is projected to be the seventh largest globally by 2030. Over recent years, the country has returned to investment grade, and sustained strong growth throughout the global recession, largely on the back of healthy domestic consumption. Its GDP growth is forecast to be 5.7% this year and picking up further in 2015. However, around 32 million Indonesians still live below the poverty line and the country's economic potential is held by back by high levels of corruption and infrastructure bottlenecks.

3. Dynamic society

As a military coup undermines the political stability of Thailand, and questions persist about quasi one-party-rule in Malaysia and Singapore, Indonesia's democratic transition has largely been hailed as successful. Since the fall of Suharto, and the end of his nepotistic 31 years in power, Indonesia has moved from centralised rule to a boisterous democracy. Vote buying and "money politics" have marred past votes, but the country's elections are largely free and fair and the country boasts a dynamic civil society and one of the most vibrant and critical press corps in Asia.

In a parliament that is dominated by individuals who rose to prominence during the Suharto era, corruption remains a huge problem. But the country's anti-corruption body, the KPK, has made incredible gains. The "graftbusters" have jailed some high-profile politicians and figures in recent years, just this week putting Akil Mochtar, the former head of the constitutional court, behind bars for life.

There are around 216 million Muslims in Indonesia, more than in the whole of the Arab world. (AP Photo/Achmad Ibrahim) Photograph: Achmad Ibrahim/AP

4. Moderate Islam

With a population of 240 million people, 90% of whom are Muslim, is often held up, alongside Turkey, as an example of the compatibility of democracy and Islam. Though the Middle East may be the centre of gravity for the Islamic world, Indonesia has more Muslims than that entire region. Since the fall of Suharto, when both political and religious freedoms were curtailed, democracy and Islam have thrived. Muslims in Indonesia predominately practise a moderate form of Islam, and during recent years the government has worked hard to cripple extremist groups, such as those behind the 2002 Bali bombings. Indonesia's constitution protects religious freedom but under Yudhoyono – whose coalition includes Islamic-based parties – religious intolerance against Christians, Shia Muslims and Ahmadis has been on the rise.

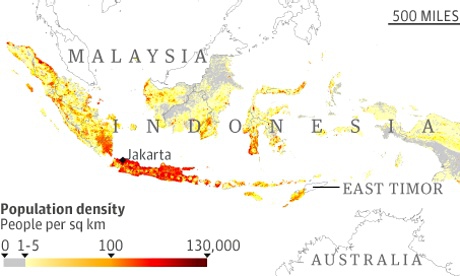

The Indonesia archipelago includes more than 17,000 islands. Guardian Graphics

5. National Unity

Poised to play a greater role on the global stage, politically and economically, Indonesia needs a leader who can unify one of the world's most diverse nations. This is a country that stretches across more than 17,000 islands, with hundreds of ethnic groups and languages – and yet has held together well since its foundation in 1945. In a globalised world beset by schism, separatism and break-up, it stands as an example of the benefits of togetherness. Both leading candidates have a nationalist thread to their argument. Whichever wins, the world may face a more assertive, determined Indonesia after 9 July.

No comments:

Post a Comment