http://www.guardian.co.uk/society/2013/apr/27/profumo-affair-sex-1963

Vanessa Thorpe

In 1963, the Profumo affair and the sexual revolution took Britain by storm in a few short months. Half a century on, we trace the long-term impact of a tumultuous year.

Mandy Rice-Davies and Christine Keeler leave the Old Bailey after the first day of the Stephen Ward trial concerning the Profumo scandal Photograph:Hulton-Deutsch Collection/CORB

One of Philip Larkin's best-known poems, Annus Mirabilis, picks on 1963 as the year when sex was invented in Britain. The poet may not have been entirely serious, but his claim has a lot to support it. In the summer of that year, due to a convergence of cultural and political events that centred on London, an impression of both glamour and seedy intrigue was created that has never quite gone away.

Fifty years ago last Wednesday a feisty blonde call girl, Mandy Rice-Davies, was arrested at Heathrow airport on her way to Spain. She was charged with possessing a fake driving licence and she spent the next nine days in Holloway prison. Her incarceration for this paltry crime turned out to be one of the last factors in the unravelling of the Profumo Affair that in a little over a month would have forced the resignation of the war minister over his affair with Christine Keeler and revealed a world of vice and deceit at the heart of the British elite.

In the early days of that summer, while John Profumo was still battling to salvage his reputation, other events were also helping to change the way the country saw itself. In America the first Bond film, Dr No, premiered, finally selling the idea that the British could be sexy, while in June a British-made contraceptive pill became available for the first time. And, all the while, the hits from the Beatles' first album were being played throughout the country, as the Fab Four were packaged and made ready for their triumphant American tour in the first weeks of 1964.

"It was the beginning of the separating out of babies from sex," comments novelist Fay Weldon. "The pill made an enormous difference to women quite quickly and Keeler, although she was naughty, became a sort of role model, so that you would have been quite pleased if she came to dinner, as long as she stayed away from your husband."

Larkin's poem's opening lines –

"Sexual intercourse began

In nineteen sixty-three

(which was rather late for me) -

Between the end of the "Chatterley" ban

And the Beatles' first LP"

– also refer to the lifting of the ban on Lady Chatterley's Lover. Since the obscenity trial over DH Lawrence's explicit novel in 1960, unexpurgated copies were now readily available – further evidence of how liberated the country was becoming. But it was to be another trial – the pivotal case in the Profumo scandal – that dominated the headlines half a century ago and has now caught the eye of Andrew Lloyd Webber. The composer has begun auditioning for a new musical, Stephen Ward, to be produced next year. Written by playwright Christopher Hampton, it is based on the mysterious life of the society osteopath who was charged in June 1963 with pimping for both Rice-Davies and Keeler.

"Stephen Ward really intrigues me and was a fantastically interesting character," Lloyd Webber has said. "The most popular man in London who ended up with absolutely nobody. I think he was the fall guy."

The Profumo affair began with rumours that Harold Macmillan's war minister had slept with Keeler while she was also seeing a military attaché at the Soviet embassy, Yevgeni Ivanov. The issue became a public matter once it was claimed national security had been compromised. So Profumo stood up in the House of Commons in March to deny the affair.

During April and May the politician kept up a front, suing foreign publications that had relayed the rumours, such as Italy's Tempo Illustrato, which offered unqualified apologies in the high court, and the French magazine Paris Match. A Guardian report from 50 years ago shows Profumo was still gamely sticking up for press freedom too. "I don't grumble at all," he told Berkhamsted Young Conservatives. "I am all in favour of a free press and the moment we start to try to control it in any way, we would be in serious trouble."

Keeler had first met Profumo three years before at Cliveden, the country home of Viscount (William) Astor, where her friend Ward was staying in a cottage on the estate. Viscount Astor also owned this newspaper at the time and his younger brother, David, was editor, so at least part of Fleet Street had access to the information that Profumo had lied about his affair. The net finally closed when a chief inspector visited Rice-Davies in prison to offer her a deal. He made it clear that if she helped the police with an investigation into Ward, she would be released.

On 5 June Profumo confessed to parliament that he had lied, and tendered his resignation. Three days later Ward was arrested and that weekend theSunday Mirror printed a letter from Profumo to Keeler that had been circulating among journalists all spring. Known as "the Darling letter", it made it clear the pair had been lovers.

The social historian David Kynaston was not yet in his teens in 1963 but he remembers the sensation around the trial. "It certainly sold newspapers and in the summer holidays that year I noticed my father reading a paperback calledScandal:63 that had been rushed out. The Profumo affair was one of the things that switched the English default position on politics from deference to scepticism, if not yet to cynicism," he said.

Larkin's tongue-in-cheek lines from Annus Mirabilis express the feeling that he had missed out by being too old and Kynaston suspects this sense of missing out is central to the myth of the birth of the permissive society. "We still tend to see that era through the eyes of the young," he argues. "Youth culture was not widespread yet, and although higher education was slowly expanding, students were just a minority. We should not really privilege the young in history, although it is the new that always attracts attention."

Kynaston agrees there was a surge of social movement, but is wary of assuming that changes in London were mirrored across Britain.

"I was at university in the early 1970s when my great friend from Lancashire said to me, 'I can tell you, David, the 60s never happened in Blackburn'," he recalls. The geographic divide is one the Liverpudlian poet Roger McGough felt keenly too. "I was brought up Catholic in the north and a lot of my work has been about that feeling of being outside, looking in," he said. "I may have been in [60s band] the Scaffold and part of the Mersey Beat, but it all seemed to be happening in Carnaby Street. Then, when I did get down to London, it was always happening somewhere else. I guess there were some people who for a time, due to drugs or drink, were able to see themselves at the centre of things."

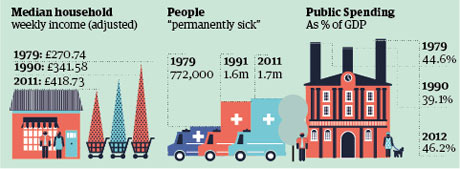

In Liverpool though, remembers McGough, it felt like the end of things, as industries shrank and the docks closed. "The 60s were a party being given by the government to hide what was really going on," he said. Britain, Kynaston explains, was still predominantly working class in 1963 and "still very much an industrial economy".

Yet the modern young woman, personified by Julie Christie's adventurous character in the 1963 film Billy Liar, was sold to the public as the face of the future. For Kynaston, though, this notion of sexual liberation was at least partly a construct of the entertainment and advertising industries. (This was also the year that David Ogilvy's influential book Confessions of an Advertising Mancame out, celebrating new sales techniques.)

Feminist writer and psychotherapist Susie Orbach agrees that, while some women embraced modern sexual freedom, many more were held back by convention for at least another 10 years. "This was pre Women's Lib, so women might have seen it in terms of their own agency, but the idea that was really being sold, along with the glamour of sex, was still marriageability," she said.