http://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2014/nov/12/how-to-paint-happiness-a-masterclass-from-matisse

Jonathan Jones

In 1905 Henri Matisse created the most perfect image of bliss. This is the story of Le Bonheur de Vivre

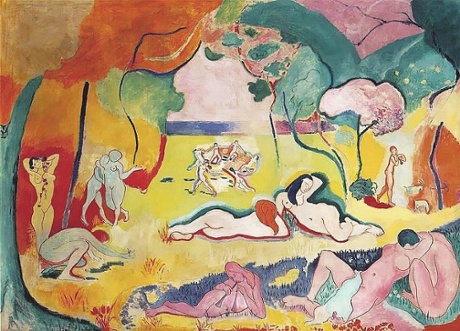

‘Sheer ecstatic happiness awaits’: Matisse’s Le Bonheur de Vivre. Photograph: © 2014 Succession H Matisse/Artists Rights Society, New York/The Barnes Foundation

In the early years of the 20th century Henri Matisse painted a manifesto for happiness. The Great War was still in the unimaginable future. The Depression was even further ahead. If you belonged to the affluent classes of the western world in 1905 you had every reason to be happy. Matisse was bold enough to say so.

Le Bonheur de Vivre was begun in 1905, completed that winter, and shown at the Salon des Indépendants in Paris in March 1906. This revolutionary masterpiece is a cry of primal joy whose title translates as “The Pleasure of Living”. Matisse also called it La Joie de Vivre, and in English it’s often known simply as The Joy of Life. This big picture, nearly 2.5 metres wide, was instantly snapped up by the American collectors Gertrude and Leo Stein and today it’s in the Barnes Foundation, Philadelphia.

Sheer ecstatic happiness awaits anyone who lets this painting do its work.

An opening like an eye, or a vagina, unfolds gently out of a woodland whose leaves are silken veils of blue and violet, russet and gold, green and brown. Under the trees, as the mind of the onlooker follows a succession of stage-sets towards a distand band of blue sea under a coral sky, people pursue pleasure with a kind of enchanted purity. Their sports are sacred. A couple embrace in the foreground, naked and mysteriously conjoined at the head as if their bodies have become one, while a nude musician plays her pipes. Another naked lover leans down to pick a flower, to add to the red garlands that decorate his girlfriend’s breasts. All of these bodies are marked in simple lines, with slits for eyes and dots for nipples and pale, almost blue or violet skin. These people are curvaceous creatures of unthinking bliss, glorious brainless blooms in the landscape of paradise.

Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon. Photograph: Stan Honda/AFP/Getty Images

Le Bonheur de Vivre is the last great perspective painting. For about 450 years, European artists had been using the science of perspective discovered in the Renaissance to map out the illusion of depth on canvas. Just a year after Matisse unveiled his paean to pleasure, his rival Picasso would mock it in Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, an aggressively unhappy painting that pushes its jagged figures of glaring prostitutes to the front of a picture space closed off by shards of crystal blue. Cubism was about to destroy the illusion of the picture. But Matisse makes emphatic – though cheerfully inconsistent – use of perspective, in a way that is crucial to his artistic dream of happiness.

This painting, so revolutionary in its free, expressive use of colour and abstracted simplification of the human form, uses traditional pictorial space to create a world we can enter, a landscape the mind can play in. As we gently move, like a film camera, into its deep, warm bath of pictorial space, we see the dancers in the distance, the piper in the woods, the empty beach. A world of bliss lets us fall into it, slowly, with a soft landing. What wondrous place is this?

It is Arcadia, not the real region of that name in Greece but a mythic pastoral realm of happy shepherds and nymphs that has been imagined by poets and painters ever since the Greek writer Theocritus wrote his Idylls in the third century BC. If Matisse echoes Renaissance perspective in Le Bonheur de Vivre, it is because he wants to emulate Renaissance artists in creating a happy dream world of art, a blissful pastoral fantasy.

For example, the woman losing her head – literally – in passion at the right foreground of this painting echoes the pose of a nude in the right foreground of Titian’s Bacchanal of the Andrians (1523-4). Titian’s painting celebrates sex and wine and self-loss. It portrays an orgiastic drunken party in the countryside, and the reclining woman is experiencing total ecstasy. His pipe players recall another vision of rustic happiness by Titian, the Concert Champêtre, which, like all French artists, he knew well – it’s in the Louvre.

Titian’s Concert Champêtre. Photograph: Corbis

For there is a long tradition in European art of portraying happiness. The landscape of bliss is imagined in this tradition as a pastoral picnic, bordering on an al fresco sex party. Le Bonheur de Vivre, for example, deeply resembles Watteau’s 18th-century painting The Embarkation for Cythera, in which lovers melt into a leafy world whose soft, yielding colours are intensely erotic. Watteau and Matisse both use colour to drug and seduce the mind into a sensual wonderland.

Matisse draws on millennia of imagining happiness to create the joyous paradise that is Le Bonheur de Vivre. Yet he did this just at the moment when modern art was about to question such ancient ideals as beauty and the assumption that art should be enjoyable. Picasso’s art is edgy, even ugly, and restless. The Expressionists took Matisse’s colours but made them anxious and uneasy. The golden bowl was cracking.

Matisse’s pursuit of happiness has been held against him. In 1908 he explained the thinking behind paintings like Le Bonheur de Vivre in what was to become a notorious proclamation of bourgeois hedonism: “What I dream of is an art of balance, of purity and serenity, devoid of troubling or depressing subject matter, an art that could be for every mental worker, for the businessman as well as the man of letters, for example, a soothing, calming influence on the mind, something like a good armchair that provides relaxation from fatigue.”

These words got Matisse’s happy art a bad name. Picasso mocked them, as did other avant garde artists. After 1914 the idea that art could just be a soothing accompaniment to an after-work cocktail seemed absurdly inadequate to the struggles and horrors of the modern world.

But Matisse stuck to his guns. Anyway, he kept on enjoying himself. In the 1940s, in Europe’s darkest hour, he started cutting up coloured paper to create Arcadias that are just as free and pure and magical as Le Bonheur de Vivre. Do these cutout idylls appear pathetically evasive and escapist, a flight into colour from the realities of the Holocaust and Hiroshima? No, they do not. Rather, Matisse appears the guardian in the darkest times of something that human beings need to be able to imagine and believe in. Happiness is a human right; Matisse speaks up for it beautifully.

No comments:

Post a Comment